Orange and black: the forgotten history of black servants at the court of Willem V

Child slaves, renamed Cupido and Sideron, ended up in the Dutch court as boys and spent the rest of their lives serving the royal family. Gordon Darroch visited a fascinating new exhibition about their lives in The Hague.

You can see them in a painting from 1781 by Hendrik Pothoven, titled ‘the Buitenhof during The Hague circus’: two tiny, finely drawn figures that stand out among the entourage of Stadhouder Willem V for their striking outfits and prominent turbans, but above all for being the only black faces in the crowd.

These were the servants, Cupido and Sideron, who arrived at the stadhouder’s court as children in the 1760s and whose fates were bound up with the turmoil that engulfed the House of Oranje-Nassau following the French Revolution. Their story is the basis of a fascinating exhibition at The Hague’s Historical Museum that trains the spotlight on a point where the elegant traditions of courtly life cross with the murkier aspects of colonial history.

Cupido and Sideron were far from the first black servants to appear at a European court. Slave traders had presented children from the colonies as gifts for at least a century, not just to noble families but to sea captains in the trading companies as a kind of bonus payment.

Collectors

Some of these so-called ‘present slaves’ were sold on, often to German aristocratic households, for sums as high as 500 guilders, equivalent to a year’s salary for a high-ranking servant. In France, the Duke and Duchess of Orléans were avid ‘collectors’ of African children as young as four.

Amsterdam became a centre for this unofficial trade in human ornaments, says historian Esther Schreuder, whose extensive research for her book, Cupido en Sideron, forms the backbone of the exhibition. ‘There was a market in children – present slaves, as they were called, were brought to the Republic where they could be sold or given away. But it wasn’t advertised openly.’

Most of these children arrived from the Dutch Republic’s Caribbean territories or the west coast of Africa. Sideron was born into slavery in Curaçao and baptised in the Catholic parish of St Anna in Willemstad with the names Guan Anthony (though as a servant in the House of Orange, he had to observe the Protestant faith).

How he came to The Hague is unclear, but it is likely to have coincided with Willem V taking his place in the States General and the Council of State in 1763, when he reached the age of 15. Cupido arrived three years later, probably as a gift from Jan Pieter Theodoor Huydecoper, head of the West-Indische Compagnie. His birthplace was recorded few years later as Guinea, and on joining the Oranjes’ household he was given the name Willem Frederik Cupido.

Neither would ever see their birthplaces again and all trace of their original names and families swiftly vanished.

The status of these children was, as Schreuder points out, far from straightforward. ‘As children, they were completely dependent on the place where they ended up,’ she says.

Playthings

The flamboyant names reflect the fact that they were often acquired as playthings or accessories, but as they grew up they had to secure a place in the household. Cupido and Sideron received an education, learning to read and write in Dutch and French; they were given dance lessons, which were otherwise reserved for pages, and taught to shoot.

A painting from 1770 by TPC Haag, The Shooting Party at Het Loo, depicts the two boys accompanying the prince on a day’s hunting at the Oranjes’ Gelderland retreat. At the age of 17 they were put on the wage bill, receiving 156 guilders a year. By comparison, a coachman earned 90 guilders in the same year, a lackey 120 guilders and a page 140 guilders.

Their prospects were undoubtedly better than they would have been in the colonies. Slaves brought to the Dutch Republic who had not been sent back within a year were automatically freed.

This law, introduced to prevent slave uprisings, meant that long before they reached adulthood, Cupido and Sideron ceased to be items of property and could look forward to joining the ranks of paid servants. (Others were less fortunate; newspapers sometimes carried adverts offering rewards for the return of negers who still lived in de facto slavery, unaware of their rights.)

For a nobleman in the Dutch Republic, a black manservant was a walking statement of colonial power and status. Nowhere is this more obvious than in Jacques André Joseph Aved’s portrait of William V’s father, William IV, which depicts the stadholder standing in full battle dress while his valet, Jean Rabo, sits on his haunches on the fringe of the picture, holding his master’s helmet and gazing reverently up at him.

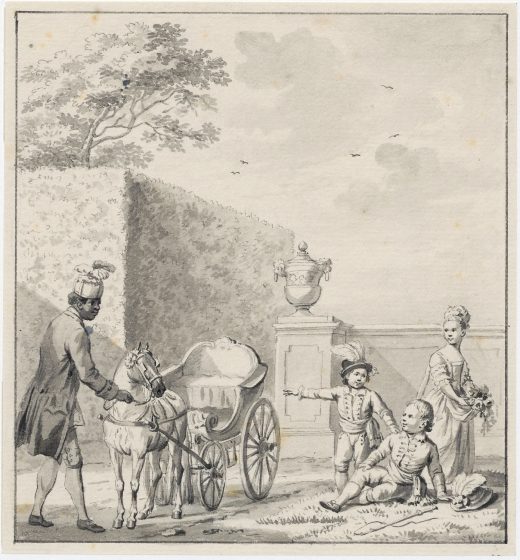

Shortly after arriving at court Cupido and Sideron were painted in full servant livery, complete with feathered turbans, and clutching tea trays, suggesting they had a strong curiosity value. They would be painted half a dozen more times during their childhood.

As adults they had a status apart within the household. On a list of staff from 1764 Sideron appears at the bottom as ‘The Moor Guan Sideron’. Like all black servants, regardless of origin, they wore a turban as part of their official dress. Though their duties and rank were comparable to the pages, that term was reserved for Dutch aristocratic children; to begin with, at least, Cupido and Sideron had no designation other than moor and neger.

Etiquette

But as their careers progressed, the pair earned the trust and respect of the court. In a society where codes of etiquette governed every aspect of life, rule number one was an absolute prohibition on ‘insults or any names that may damage each other’s honour or reputation’.

Name-calling or personal abuse would be ‘exemplarily punished’, so overt racial slights would have counted as a serious breach of protocol. In 1782 they were promoted to the personal staff of Willem and Wilhelmina as chamber servants (though they retained their turbans).

When the royal household fled to Britain in 1795, as French revolutionary armies encroached on the Republic’s borders, Cupido and Sideron were among the family’s reduced entourage. The latter was by then Wilhelmina’s first valet de chambre, with ultimate responsibility for arranging her apartment, and stayed throughout the years of exile, leaving only after Wilhelmina had made it safely to the Oranjes’ German palace at Oranienstein.

Cupido was one of dozens of servants Willem sent back within months of arriving in London, as financial duress forced him to cut his staff drastically, and then discharged from the servants’ temporary home in Brunswick.

As a refugee in Germany his position was precarious, but by the time he rejoined the royal household in Oranienstein he was engaged, to Catharina Löwe, and married her in January 1802. At his wedding he was announced as ‘a servant in the household of the prince of Oranje-Nassau and a moor’, with no reference to his origins.

Later that year Catharina gave birth to a daughter, Sophia Wilhelmina Cupido (two other children died before reaching adulthood). Schreuder traced Sophia’s family tree and found dozens of direct descendants living in the Netherlands today.

Handwriting

One surprise for Schreuder was how many written documents the two servants left behind, especially Sideron, whose meticulous handwriting is instantly recognisable.

Many are formal records relating to the household accounts, but occasionally a glimpse of their characters breaks through. Sideron appears to have been a model of dependability – on the journey back from England he was given charge of six women and five children in the party, and after his death in 1803 Willem wrote to his mother that Sideron was ‘one of those old servants who will never be replaced’.

‘He was a very elegant man, I think he was an ideal servant for Wilhelmina,’ says Schreuder. ‘Cupido was more vain. He kept running up debts with his clothes bills.’

The question remains as to how much two servants, who were cut away from their roots as children and whose identities were wholly defined by the royal household, could really be described as free.

Quite possibly it never occurred to them to seek their fortune elsewhere. True freedom in the 18th century was the preserve of a tiny elite and Cupido and Sideron’s stories are evidence that black servants were not disadvantaged within the household staff.

It is too simplistic to call them slaves, says Schreuder, who prefers the term ‘privileged dependence’. ‘If they’d wanted to leave, Willem V couldn’t have stopped them. But they had no family here and they had a lot to lose: their pension, free medical care, half a bottle of wine a day. A lackey who left the palace had opportunities elsewhere; for them the opportunities were fewer. But I’m cautious about it in the book, because we don’t know what might have happened.’

African Servants at The Hague Court is at the Historical Museum of The Hague (Haags Historisch Museum) until January 28 2018.

Esther Schreuder: Cupido en Sideron: twee moren aan het hof van Oranje is published by Balans

You can comment on this article via our Facebook page

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation