A suitcase full of secrets found in Amsterdam’s Jewish quarter after 70 years

The discovery of a suitcase filled with photographs and paintings and hidden in a cupboard in an Amsterdam flat was the beginning of a story stretching back to 1920s Berlin. Gordon Darroch unravels a mystery which plays out across the globe.

Cities are shaped by their past: it courses through them like blood, unseen but vital. Charlaine Scholten’s boyfriend told her about the suitcase in his attic shortly after they started dating last February. It was a hard brown leather case, weighing about 30 kilos, familiar from those black-and-white photographs where cases are piled high on the quayside behind families waiting to board passenger steamers for a new life across the ocean. When Charlaine sprung open the brass clasps, it began a year-long quest spanning three continents and 70 years of history.

Her brother-in-law had found it while renovating an apartment building in Amsterdam’s Beethovenstraat in 2009. ‘It was in a meter cupboard, shoved behind an old chair and beneath a bundle of old clothing,’ explained Charlaine, 26, who works at DeLaMar Theatre. ‘It was clear from where it was placed that it wasn’t meant to be found. It was a heavy old leather hardboard case, very heavy, and lined with a very fine material. When my brother-in-law opened it up everything inside was in perfect condition.

‘His boss was just going to throw it away but he said “you can have it”, so he took it home and gave it to my boyfriend, and since then it’s been sitting in his attic.’

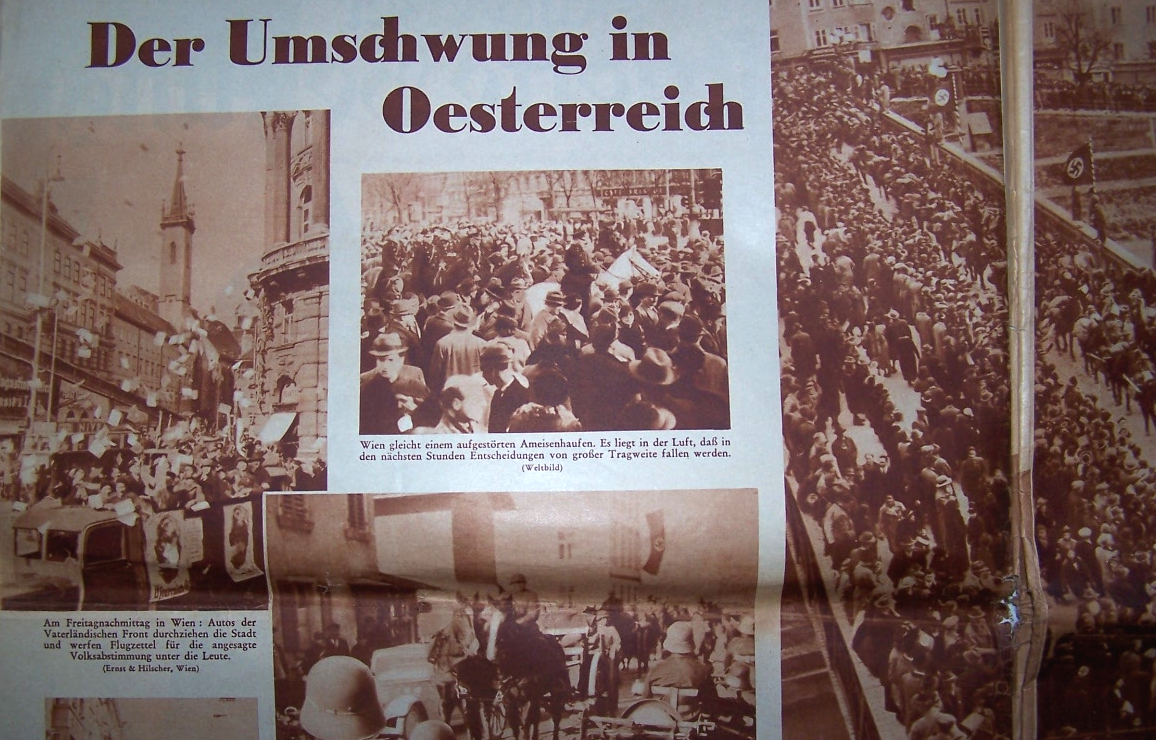

Six years had passed when Charlaine went up to the attic and the case was opened again. Inside she found a neat bundle of German newspapers, some postcards in German and, most intriguingly of all, a collection of photographs, sketches and oil paintings.

Many of them were self-portraits of a raven-haired woman of arresting beauty, with firm cheekbones and piercing eyes. The postcards gave the artist’s name as Emmy Porges and mentioned a relative called George Porges. The only other significant clue was the newspapers: copies of the Schweizer Illustrierter Zeitung, a weekly picture paper published in Zurich, with cover dates between 1933 and 1940.

Charlaine grew up listening to her grandmother’s stories of life under German occupation. ‘She lived through the war in a village just outside Amsterdam,’ she said. ‘People who had been conscripted to go and work in Germany fled to the farms, or they came from Amsterdam looking for food and milk.’ And now she had a wartime mystery of her own to uncover. She resolved to track down Emmy’s family, return the case to them and and find out why it had been hidden in the Beethovenstraat.

German enclave

Porges is a Jewish name which in pre-war Europe was concentrated in Prague and Vienna, with offshoots across the German-speaking world. After 1933, when Hitler became Chancellor, German Jews fled across the border to the Netherlands. The apartments on Beethovenstraat, built less than a dozen years earlier, quickly filled up with refugee families until it was virtually a German-speaking enclave.

After the Germans invaded in May 1940, the area became a focal point of repression and violence: the tram stop on the Beethovenstraat was the departure point for 18,000 deported Jews, and a monument on the corner of the Apollolaan marks the spot where 29 resistance fighters were mown down by the firing squad in reprisal for the murder of an SS officer.

It seemed as if Emmy Porges had fled Amsterdam in a hurry when the Germans arrived, bundling her most intimate personal possessions into the old suitcase and secreting it in the meter cupboard. Perhaps she hoped to return once the war was over, pick up her paintings and start over, but either died in the death camps or was unable to come back. That was the most obvious explanation, but as the real story emerged, it proved to be wrong in almost every detail.

Last May Charlaine enlisted the help of her mother (‘she’s very good at archiving’) to try to track down Emmy’s surviving relatives. ‘We tried Google but that didn’t get us very far,’ she said. ‘Amsterdam has records of where everybody lived since 1900, but there were no Porgesses at numbers 48 or 50 on the Beethovenstraat. Then we widened our search to Hamburg, where we found a number of families called Porges who lived there in the 1930s, including an Alice Porges. And that led us to Haydee.’

While Charlaine and her mother were tracing Emmy’s relatives in pre-war Hamburg, over in Buenos Aires, Haydee Fabian, a 70-year-old retired biochemist, was joining the dots on her own family tree. She knew her family had fled Nazi Germany and been dispersed all over the Americas and New Zealand, and her research had put her in touch with a cousin, Frank Meier, living in Florida. Frank had been born in Hamburg in 1928: Alice Porges was his mother. She had six sisters, one of whom was Emmy.

Sheer luck

‘It was sheer luck that our paths crossed,’ said Charlaine. ‘If we hadn’t been able to follow in Haydee’s footsteps we probably wouldn’t have found the family.’

Nobody in the family knew the suitcase even existed, Haydee said. ‘Charlaine contacted me through the GENI website, asking for help in finding living relatives of Emmy Porges, because they had found a very well-preserved suitcase with the belongings of Emmy and perhaps of her near family hidden behind a closet,’ she said. ‘I was astonished that something like this could happen so many years after the end of the war, and happy that Charlaine was trying to find a connection through the family tree.’

Frank Meier, now 87, fled to Amsterdam with his parents in 1932, when he was three years old. The family found an apartment on Albrecht Dürerstraat, two streets from the Beethovenstraat. Most of the other sisters stayed in Germany and were deported to the camps.

‘A lot of Jews in the 1930s didn’t think Hitler would do anything really bad,’ Frank said on the phone from Florida. ‘Nobody thought it would turn out the way it did. We escaped, but my aunt Leni, her husband and their two children, Peter and Sonya, were all shipped to Auschwitz. Uncle Alfred survived and came to live near us in Canada, but his family were all dead.’

Having escaped the Nazis once, Alice and her husband, Max, wasted no time when Germany invaded the Netherlands on May 10, 1940. ‘My mother had a better sense of things than my father,’ Frank said. ‘He believed the Germans wouldn’t take Holland – he’d say, “What are they going to do in Holland: come and fetch the cheese?”

‘She came home the day the Germans arrived and said, “We’re getting out of here”. Someone drove us to IJmuiden and we boarded a boat to England that night. That was where I lived during the war.’

Berlin

Emmy Porges, however, neither fled across the Atlantic nor perished in the gas chambers. By the time the war broke out she was already dead. Alice only occasionally spoke of her sister, but Frank believed she had died some time in the mid-thirties while living in Berlin. ‘I know very little about her except one of her beautiful paintings hung in our living room in Amsterdam,’ he explained. ‘Fortunately for her, she escaped the Holocaust and died before all the Jews were shipped to Auschwitz.’

Alice Meier died in 1983 in Montreal, Canada. During the war the family were separated: Frank grew up in London with his mother, but his father, Max, and his brother, Wolfgang, were sent to Canada shortly after landing in Britain.

‘The English thought we were 99% okay, but there was a doubt in their minds that there might be some spies among us,’ said Frank. ‘So they were all sent to Canada, including my brother who was 16. They were interned in a rural facility in Quebec province out in the wilderness. They were released in 1944 and my father ended up living in Montreal.’

When the war ended in 1945, Alice and Frank boarded a Cunard liner for Canada, where they were reunited with Max and Wolfgang in Montreal. The past was a distant country, separated by the Atlantic ocean and the horror of the Holocaust. Max Meier set up an import business in Montreal, but died just nine years later of a heart attack, aged 57.

Wolfgang changed his name to the less German Fred Richard Maitland, enlisted in the Canadian army and eventually moved to Chicago where he died in 1995, at the age of 72. The suitcase in Beethovenstraat was lost in the folds of memory; the family were too busy building their new lives, if they even knew it was there at all. It might just as well have been abandoned on the moon.

Returning the suitcase

Once Charlaine had found Emmy’s relatives, the next challenge was to return the suitcase to them. ‘We didn’t think the items would survive if we tried to post them,’ she said. Frank had a solution: his daughter, Vivien, had just retired as a stewardess with Continental Airlines.

‘I used to fly into Amsterdam all the time; it was my favourite route,’ she said on the phone from her home in Texas. ‘We used to stay near the Beethovenstraat. All that time I never knew the suitcase was there, a few blocks away from where I was staying. That was the irony.’

As a former Continental employee, Vivien could claim free flights with the airline’s successor, United Airlines. ‘So I thought, I’ll go over to Amsterdam,’ she said. ‘I flew first class both ways; my best friend was on the flight serving me. After we booked into our hotel we just walked over to the place where the suitcase had been hidden.’

Charlaine brought the suitcase to the hotel that same evening. ‘That was when it hit me, the whole gravity of the thing,’ said Vivien. ‘We had been planning and organising it for months. One of my girlfriends said to me, this is like our Anne Frank moment. The idea of this beautiful, talented and independent woman leaving all this stuff behind. I looked across at my friend, and she looked up at the carpenter who had found it, and we were all crying.’

Taking a suitcase made for the ocean-going age back through Schiphol airport wasn’t a straightforward exercise, Vivien explained. ‘It raised a few eyebrows at customs. We basically had to open it up and tell them the whole story, and then they let it through.’ In March, a few weeks after returning to Texas, she drove over to her father’s house with the case.

How Emmy’s paintings came to be hidden in a suitcase in Amsterdam was a mystery. As far as Frank knew his aunt had never been in Amsterdam, and most of the Swiss newspapers were published after the date she was thought to have died. ‘It might have been one of her friends,’ said Frank. ‘Some parts of the story we may never find out. My mother never talked a lot about Emmy; we just had the painting that hung in our living room.’

One piece of the jigsaw has emerged since Vivien returned with the case. Later in March, Haydee Fabian wrote to Frank with the details of Emmy’s death, which she had obtained from the New Synagogue in Berlin. The records show that Emmy Porges died in Berlin on February 21, 1929, earlier than Frank believed, while Alice and her family were still living in Hamburg. The cause of death was given as heart failure. Emmy’s body was taken by train to her native Hamburg, where she was buried in the city’s vast Ohlsdorf Cemetery.

Emmy’s death certificate also yields some intriguing clues. The person who registered her death was Hans Robertson, one of the best known photographers of Weimar Germany, who won acclaim for his pioneering pictures of the city’s dance scene. Her last address at Rocherstrasse 16 was in the beating heart of artistic life in 1920s Berlin, a street where lawyers and doctors rubbed shoulders with artists and musicians, with a strong Jewish contingent.

It represented everything the Nazis despised and, like Amsterdam’s Beethovenstraat, became the scene of vicious repression in the next decade. The author Erich Kästner bought the house at Roscherstrasse 16 a few months after Emmy’s death and lived there until it was destroyed in a bombing raid in 1944. Hans Robertson, himself a Jew, was forced to flee to Copenhagen with his wife, a Danish dancer.

Unanswered questions

The question of who left the suitcase in the Beethovenstraat, and why, may never be answered. Someone was fond enough of Emmy to stash her paintings away in the back of a cupboard, with the intention of coming back for them some day.

‘It’s very difficult to say, but I think it was Alice’s suitcase,’ said Charlaine. ‘If you look at what was inside, it’s all family photos and mementos. Alice and Max lived two streets away, so perhaps they hid the suitcase before they fled.’ But Frank is unconvinced: ‘My mother never expressed any wish to go back to Europe after the war,’ he said.

However the suitcase came to be there, its discovery opened a window onto a period of history when darkness was spreading across Europe. Its cities were being strangled by tyranny, its people scattered across continents. And someone wanted to ensure Emmy Porges’s artworks, her postcards and memories of a brighter time, outlasted the impending nightmare.

Thanks to Charlaine Scholten’s efforts, that promise has been made good. ‘I’m so glad we did this,’ she said. ‘My grandmother lived through the war and took in people who were forced into hiding on her farm. She told us a lot of stories about those days. This felt like a way to do something in return.’

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation