Sunken history: raising the wreck of a wartime bomber piece by piece

Seventy-seven years after it plunged into the waters of the Markermeer, a wartime bomber is giving up its secrets fragment by fragment.

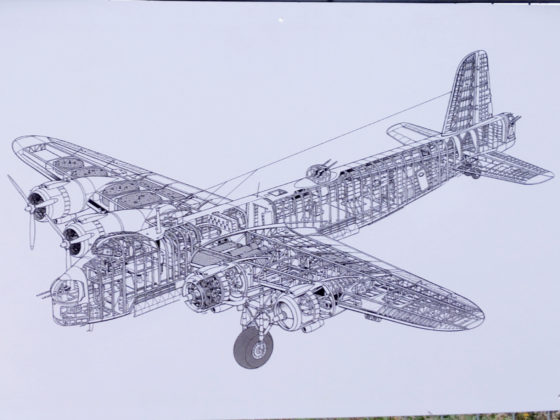

The BK716 Short Stirling plane was shot down on March 29, 1943, on its way back from a raid on Berlin. All seven crew – five British and two Canadian servicemen – are thought to have perished in the crash.

The recovery operation began on August 31, following a decade-long campaign led by families and the Aircraft Recovery Group, a volunteer organisation that specialises in recovering and identifying the wreckage of wartime planes.

The lake bed north of Almere is one of the first sites chosen for a Dutch government programme to recover between 30 and 50 aircraft and the remains of the airmen who flew in them, who are still officially classed as ‘missing’. Their families hope it will give them definitive answers about what happened to their loved ones.

Yellow buoys mark an area 75 metres square where the remains of the aircraft are scattered across the muddy lake bed. A giant mechanical digger scoops 250 m3 of sludge and water a day onto a barge before draining it over a grill. Any objects larger than 8 mm in diameter can then be cleaned, dried and examined.

‘It’s great to see this happening at last,’ says Johan Graas, head of the Aircraft Recovery Group. ‘They’re scouring an area now where we found the parachute locks, so I have big expectations that they will find human remains there.’

The clasps on the locks were closed when divers found them on the bottom of the lake, indicating that the airmen had no time to bale out before the plane struck the water.

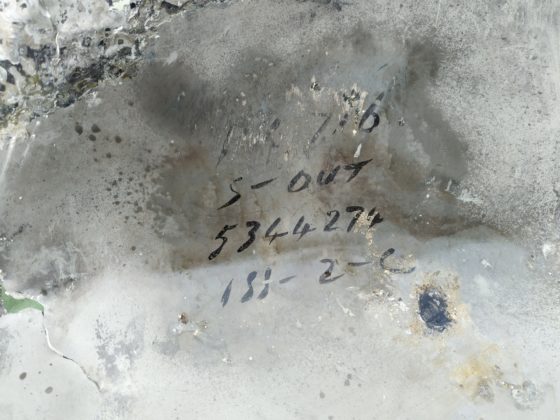

Originally the aircraft in the Markermeer was thought to be a different plane, the BK710, after a faded aluminium panel was misidentified by forensic researchers. One of the pieces recovered on the first day settled the issue: a cover of the landing gear with the serial number BK716 clearly inscribed in pen on the inside.

‘People assume these aircraft were mass produced, but not every part fitted every plane,’ says Arie Kappert, a retired aircraft recovery specialist with the Royal Netherlands Air Force who is assisting the salvage team. ‘They would write the serial number on the parts to make sure they didn’t get mixed up.’

GPS technology

The team work eight hours a day, starting at 7.30am, using GPS technology to guide the digger to the areas where the wreckage is most likely to be found. The plane hit the water at an angle and disintegrated on impact, making the recovery a painstaking process.

The force of the crash is illustrated by one of the first items hauled from the water: a lump of uncoiled rubber like a giant black orange peel that was once a tyre.

Engine parts, oxygen cylinders and a propellor are among the other items that have been found so far, as well as a spanner from the plane’s maintenance kit.

The contractors inspected the pieces carefully on the sieve to identify any explosives or radioactive instruments caught up in the haul. Any human remains found will be analysed for DNA testing so the samples can be matched with the crew’s families.

The identification of the plane is a major milestone for relatives such as 94-year-old Edith McLeod from Niagara Falls, Canada, whose older brother, Harry Farrington, was on board as navigator.

‘It’s put a lot of questions to rest, so it’s a nice feeling,’ says her daughter, Fiona Williams. ‘It was a bit unreal to find out after all this time. We’re just hoping now they can find some remains.’

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation