The Netherlands wants to lead Europe’s hydrogen strategy – but should it?

With the world hydrogen summit kicking off in Rotterdam on Monday, the Dutch are hoping to play a key role in Europe’s clean energy portfolio.

In 1959, while prospecting for oil in a beetroot field in eastern Groningen, the Dutch Petroleum Company found gas instead. The sky-high flame could be seen for miles around. In time, neighbours would learn that they were living on top of the largest gas field in Europe.

Within a few years, this hidden resource supplied 93% of Dutch households, with the excess sold abroad. But a series of earthquakes, an urgent need to decarbonise our energy economy to halt climate change, and the political imperative to be more self-sufficient, now sees the Netherlands using the very same pipeline to experiment with a potentially greener alternative: hydrogen.

Hydrogen backbone

The construction of a ‘hydrogen backbone’, executed by Hynetwork Services, has already begun, connecting industrial clusters across the country in five main locations: Chemelot in Limburg, the North Sea Port in Zeeland, the North Sea Canal, the Hydrogen Hub in Rotterdam, and the northern Netherlands, where the Hydrogen Valley cluster is being developed.

‘The Netherlands has an excellent position to develop a hydrogen economy,’ Simon den Haak, corporate communications manager for Gasunie, told DutchNews.nl. ‘We have the North Sea, which is a shallow sea which is very suitable for off-shore wind power.

‘We have ports for the import of hydrogen, for example; we have the industry which is closely related to the coastal areas of the Netherlands, [and] we have one of the most sophisticated gas networks in the world, which can be repurposed for hydrogen use,’ he said.

In fact, the Netherlands is already Europe’s second-largest producer of hydrogen (after Germany). Hydrogen, nature’s most abundant element, is a versatile resource with a higher energy storage density than electricity.

In the Netherlands hydrogen is used primarily as an industrial feedstock, such as in the production of steel and iron or to make ammonia for fertiliser. Hydrogen can also be used in a fuel cell − for transportation or backup power, for example − or burnt to raise heat. Research is underway at the TU Delft into hydrogen’s potential within the built environment.

Green hydrogen

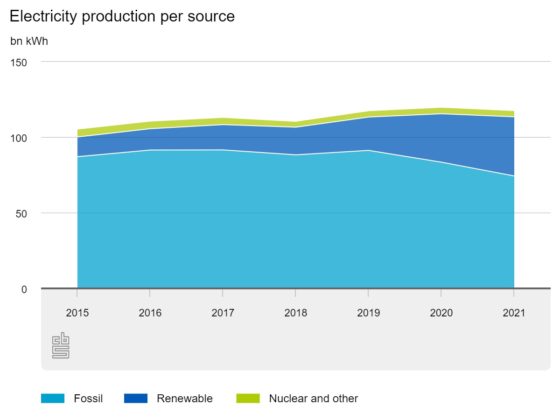

Yet Dutch hydrogen is currently part of the problem, not the solution, since most is generated using fossil fuels, accounting for 8% of the Netherlands’ CO2 output. Switching to green hydrogen, created by splitting water using electrolysers powered by renewable energy, produces no harmful emissions and was identified as a crucial step towards decarbonising industry in the European Commission’s 2019 Green Deal and in the Dutch cabinet’s hydrogen vision (March 2020).

To support this, the government has pledged to double the country’s wind energy capacity, while the EU has paid €20 million in subsidies into Heavenn, a group of inter-connected hydrogen projects in the northern Netherlands, which is due to complete in 2026.

‘It’s the quickest way for large industrial companies … to become more sustainable,’ says Den Haak, emphasising that more than half of Gasunie’s €7 billion investment budget leading up to 2030 will be in hydrogen. ‘As a small country with a very large industrial base, hydrogen is key and crucial for those sectors to keep our economy going and fight climate change at the same time,’ he adds.

Ideal testing ground

Tatiana Block, senior hydrogen project engineer at Enercy, the consultancy behind Heavenn, says that the northern Netherlands is an ideal testing ground for Europe’s hydrogen rollout, helping them explore the technical feasibility, as well as the economic benefits for the region.

‘All the ingredients that you need to develop that supply chain of hydrogen and the green economy are there together,’ she told DutchNews.nl. ‘We have the wind to provide renewable energy from the North Sea; we have a large gas transmission infrastructure … that can be reused … we have industrial and chemical clusters that can guarantee the uptake of hydrogen and we can also test the application of hydrogen.’

Electricity

Though hydrogen’s primary role will not be to serve the grid, it can be useful to decarbonise industry, heating and mobility and to power remote locations. ‘It can help manage the intermittency of the production of renewable energy such as wind and solar,’ Block explains. ‘We can store hydrogen and this can be used to balance the seasonal demand of electricity.’

But of course, electricity is also needed to make green hydrogen in the first place, and leaning too heavily on hydrogen risks aggravating the energy crisis rather than assuaging it. The Dutch Hydrogen Strategy (2020) outlined an increase of the Netherlands’ electrolyser capacity from 0.5 gigawatts to 3-4 gigawatts by 2030. Now coalition parties VVD and D66 want to double that goal.

However, with existing electrolysers producing megawatts of power, rather than gigawatts (1000 times larger), scaling up, says Block, is one of our biggest challenges. ‘The technology is produced on a small scale and is not necessarily commercially mature yet,’ she says, adding that ‘transport, the storage of hydrogen, and the safety around it is also a challenge.’

Criticism

For some, the whole project is overblown. ‘Hydrogen is over-valued as an energy carrier,’ Piet Hein Bellaar, founder of the Vereniging Thorium Energie, told DutchNews.nl. Instead, he argues in favour of increasing our nuclear power capacity.

Nuclear has none of the intermittencies of wind power, he explains, is four times cheaper, and can provide industry with the electricity needed to create hydrogen on site, removing the need for the extensive hydrogen distribution networks currently planned.

‘In my opinion, the use of green hydrogen will not grow as fast as predicted,’ he added. ‘For the next five years, it remains too expensive for the industry.’

Waste

Maarten van Andel, author of ‘De Groene Illusie’ (2018) and ‘De Groene Kans’ (2020), books which challenge prevailing strategies for decarbonisation, also believes that the Netherlands is ‘on the wrong path’ when it comes to hydrogen. ‘There’s no faster way of wasting energy than making hydrogen from it,’ he told DutchNews.nl.

‘Hydrogen gas is a substance that does not occur in nature, unlike natural gas … That means we must make it,’ he explains. ‘We can make it with natural gas or electricity – in any case, some other energy source – but when we do that, we lose more than half the energy we put into it. I think that’s a very bad idea.’

The scarcity of green energy, which Van Andel believes is long term, means we must use it wisely, and be wary of exaggerated reports of its future abundance. We would need 100,000 wind turbines – enough to circle the earth – if the Netherlands were to rely on wind energy alone, he points out.

Burning ambitions

And making (blue) hydrogen with gas and then capturing most of the carbon (CCS), he argues, is no better: ‘It’s like sweeping the dirt under your carpet and then saying you’ve cleaned up.’

The Dutch government clearly disagree. Last year they spent almost half of their budget for sustainable projects on Porthos, an offshore carbon storage project in the port of Rotterdam – a short-term solution we will quickly outgrow, says Van Andel, describing it as ‘completely senseless’.

Instead, Van Andel advocates for a bottom-up approach: ‘We must halve our energy consumption. It’s the only way,’ he says. ‘It is beneficial in every possible future scenario.’

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation