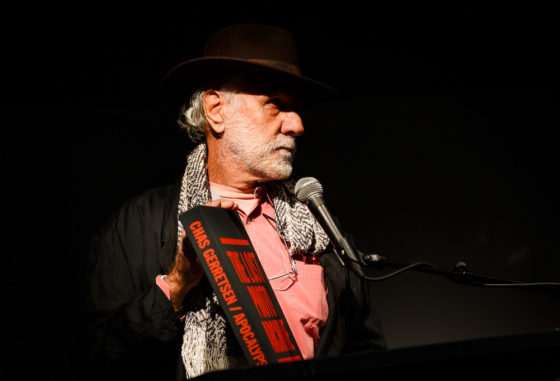

Get the picture, no matter what: A conversation with Chas Gerretsen

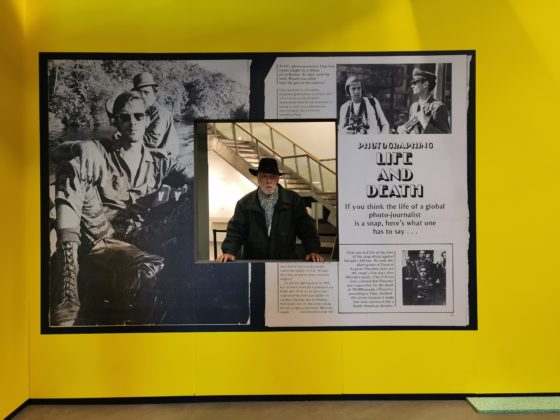

Dutch photographer Chas Gerretsen’s work is currently featured in three recent books and an exhibition at the Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam. In this interview, he discusses his experiences as a photojournalist during the Vietnam War and as a photographer on the set of the infamous 1979 film Apocalypse Now.

If you spend an afternoon chatting with Dutch photographer Chas Gerretsen you might find yourself longing to quit your day job, grab a camera, and head out into the furthest reaches of the world.

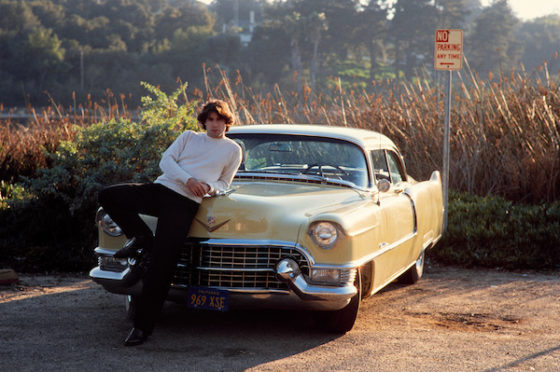

Over the course of his extraordinary career he’s worked as a crocodile hunter, a cowboy, and a conflict zone photographer who captured some of the most dramatic moments of the 1973 Chilean coup d’état. The latter earned him the Robert Capa Gold Medal for exceptional bravery. In 1989, he gave up a career as a photographer in Hollywood to sail around the world to, as he puts it, ‘everywhere where it’s warm.’

In recent years, he’s begun sharing photos from his archives on social media. His time working as a photographer on the set of the troubled Francis Ford Coppola film Apocalypse Now was the subject of a 2019 documentary. In 2021, three books were published that cover his life and career.

You grew up in Groningen and left home as a teenager to roam around Europe. Your travels eventually took you to Australia where you worked as a crocodile hunter and then you went on to do combat photography. Where did all this fearlessness come from?

I think it’s because of the curiosity in me. There’s always been this curiosity. Recently, I thought about this. When I was 11 or 12, my mother’s family had a little cottage on Schiermonnikoog, an island off the coast of Holland. I was given some money to take a bus to the ferry. My cousin’s father also gave him money. He took the bus. I hitchhiked. I did it so I could pocket the money, but hitchhiking was also exciting. It was fun and I got to meet people.

My cousin became very successful and received the Orde van Oranje-Nassau from the Queen, but he had a life I would not want for all the money in the world. Money has never been my driving force. My driving force has always been curiosity. Curiosity got me everywhere. It got me a press card which allowed me to cover a war, it got me into a nuclear centre in Buenos Aires while it was being cleaned, it got me into the White House, and it got me into Hollywood homes. It was the golden card.

In the late 1960s, you walked across the Cambodian border and into the middle of the Vietnam War. What happened next?

I walked into Vietnam in 1968 during the Tet Offensive because I didn’t have the money to buy a plane ticket, not that there were any civilian aircraft flying into Saigon. I headed into a Special Forces base camp. The guys invited me for breakfast, it was fantastic, and then they said ‘there’s some guys in Saigon who would like to talk to you.’ They put me in a helicopter and, the next thing I knew, I was seated beside a guy with an M60 machine gun. The whole approach to Saigon had been bombed flat because it was a free fire zone. Try to picture coming from western civilisation and into something you just can’t imagine.

I spent a week there being interviewed by all the military intelligence agencies. I was just a tourist, and I was enthusiastic about what I had just done. I’d gone through Southeast Asia and Cambodia. I was very happy to talk to all these people, not realising that they were using me as a spy. I was 24 or 25 years old. It was unbelievable.

You eventually found work as a photojournalist there. What was it like to go from being a tourist to taking photos of combat?

In my autobiography, I talk about my time in Vietnam and the insanity of it; the money wasted and the lives wasted for career possibilities for the higher officers. Often resupply helicopters brought too much food for the soldiers, and they just blew it all up so they wouldn’t have to carry it.

I covered a firefight in Saigon and, on the way back, I was picked up by a couple of guys in army uniforms in a Navy truck. They were working for Class One, the army’s food supply department. They had traded 20 cases of t-bone steaks for the truck and got an armoured personnel carrier for 40 cases of steaks. They invited me to a compound in Saigon and the first thing they did was show me the carrier. The major in charge was furious when he found it and said ‘Get that damn thing out of here, we’re not a combat company!’

So they asked me if I wanted it. I asked them, ‘What in God’s name would I do with a $200,000 armoured personnel carrier?’ They said, “We’ll paint it purple and write ‘press’ on it!’ I didn’t take it. Then they started filling their truck with steaks, chicken, cans of coffee, and tubs of ice cream. They took me home and started loading it into the apartment where I was staying. It was absolute insanity.

In combat zones or film sets as chaotic as the one for Apocalypse Now, you obviously didn’t have much time to deal with f-stops and whether or not things were in focus. How did you get such amazing shots?

You make sure that, depending on the available light, you’ve already set the f-stop and that the lens is wide open at 2.8 or 2.4, depending on the lens you have. The images may be sharper if you go with f-stop 8, but you hope that you can just get the picture. The only thing in your mind is to get the picture, no matter what. In combat, apart from worrying about the camera part, you have to be in the position where you can take the picture safely and survive.

You learn fast. I remember hiding behind a sign that said ‘Saigon: 24 kilometres’ or something like that. I thought it was solid concrete. When a bullet passed straight through it and I got a face full of dust, I found out that wasn’t the right place to hide.

When I was on the Apocalypse Now set, I was always looking for the best angle, but the best angle was always going to be where the film crew’s camera was sitting. So what’s the best angle after that? In front of that camera. Several times at the beginning I had to be told to get out of the way. Many of those shots were taken with the shutter speed set to a 60th of a second. I had to keep the camera very still to make sure I didn’t get a blurred photo.

You also found yourself dealing with the notoriously prickly actor Marlon Brando. What was he like?

I figured I wouldn’t get to take photos of him because Brando hated photographers. He eventually got there and introduced himself to everyone. He said, ‘Hi, I’m Marlon Brando,’ but he looked past everyone. He was always looking at something else when he spoke. It was like you didn’t exist for him.

I was eventually told he liked me and would let me take photos of him. But I always had to tell him when I was going to, so I wouldn’t break his concentration. One time I took a photo of him looking down at a container where Martin Sheen’s character was being held captive. I asked him politely to look up, and he said, ‘don’t you ever try to direct me.’

I didn’t put this in any of the books, but Francis wanted one more day from him on the set, and I think he demanded $100,000. Francis was almost nearly broke and financing the film out of his own pocket. He refused, so Brando spent the day having photos taken across the river by his friend, a photographer named Mary Ellen Mark. We were all working and could see them over there. That’s how you tell someone to go umpf themselves.

And then there was Dennis Hopper. It’s been said that his character in the film was based on you.

He was originally supposed to play a different character named Captain Colby. One day I was told to go to Francis, and he asked me ‘how would you dress a photojournalist?’ Dennis came in, and he had one camera, a Nikon, with plastic film canisters taped to the straps. I said, ‘no, come on.’ When I was in Vietnam, we had a bag with three or four cameras with us if we could afford them. Dennis refused. He only wanted one camera.

He was a photographer, his photos were hanging in a museum of modern art in New York, and that’s the way he would do it. It took Francis two weeks to convince him he wasn’t playing a still photographer visiting Vietnam, he was supposed to be a rugged combat photographer. I don’t think he was modelled on anybody, but he was generally crazy like many of us.

On the cover of one of your books, Apocalypse Now: The Lost Photo Archive, there’s that iconic photo of Martin Sheen rising up out of the water to go kill Brando’s character. Do you remember that night? Were you both down there freezing cold and completely miserable?

In the Philippines, it’s freezing warm. It’s often 25 C at midnight. But when I do something, I do it because I enjoy it. I cannot imagine one moment in Vietnam, in the Philippines, or in my life where I didn’t enjoy it. When I stopped enjoying it, I left. When I was in Cambodia toward the end of 1970, I left because nearly everybody around me was already dead.

I was working alongside around 30 people and something like only five were still alive. I realised I wasn’t going to make it out of there, so I left. But I enjoyed the excitement, I enjoyed the people, and every day was something new. When I stopped enjoying Hollywood, I left that too.

Hollywood is a very vicious place. You can’t go there and just waltz into a brilliant career. There’s plenty of people waiting tables.

The normal thing there is that when someone tells you they’re an actor or an actress is to ask ‘what restaurant?’

You’ve since spent over three decades sailing around the world. What are some of the places you’ve visited and situations you’ve encountered out there?

I’ve been everywhere, more or less, or everywhere where it’s warm, at least. New Guinea, Northern Australia, New Zealand, and all over Southeast Asia. We’ve also sailed across the Indian Ocean and over to Chagos. We spent five years in Africa; in Tanzania, Kenya, South Africa, and Madagascar, which was fantastic. Visiting South Africa was the coldest we’ve been in 31 years, but it was nice. It’s a fascinating country.

One time we were on my sailboat anchored in the ‘Honey River’ in northern Madagascar and here came a dugout. A man in it had an infected foot, and there’s no doctor within 100 kilometres. On a sailboat, you always have all kinds of medicine if you get sick, so there I was taking the pus out of a guy’s foot. He paid me in honey. You’re always learning out there.

So where to from here? Do you want to keep writing and doing photography?

I would like to write about my sailing life, but I would need to know that somebody is interested. All of my experiences in Cambodia, Vietnam, and elsewhere were all bottled up in me. I would sometimes tell charter guests on our boat about them, and they would ask, ‘why don’t you write a book?’ I didn’t want to write a book without having a publisher. I originally wrote my autobiography in English, and it was turned down by the first five or six publishers. It was finally translated into Dutch and released. I would love to see the English edition get published.

It’s been a fascinating life. I’m in Germany right now where everything is clean and perfect. I once did a documentary about Sun City, Arizona. I asked one of the residents what he liked about it. He said, ‘it’s the peace, the neatness, and everything is so clean. It’s like we’re in heaven.’ Those are the parts I intensely disliked. For most people, it would be ideal. For me, there’s no excitement. Here in Bavaria, it’s beautiful, but too clean and too safe. You don’t live here. You exist here.

Chas Gerretsen’s work is the subject of Starring Chas Gerretsen, an ongoing exhibition at Rotterdam’s Nederlands Fotomuseum that continues to 22 April 2022.

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation