Now you see me Moria: museums unite to make Lesbos refugee crisis visible

Opening on Friday at Foam Amsterdam is an exhibition of photographs taken by refugees inside the infamous Camp Moria on the Greek island of Lesbos. But the exhibition is far from exclusive, with new venues opening each week. DutchNews.nl finds out why Now You See Me Moria has museums breaking with convention.

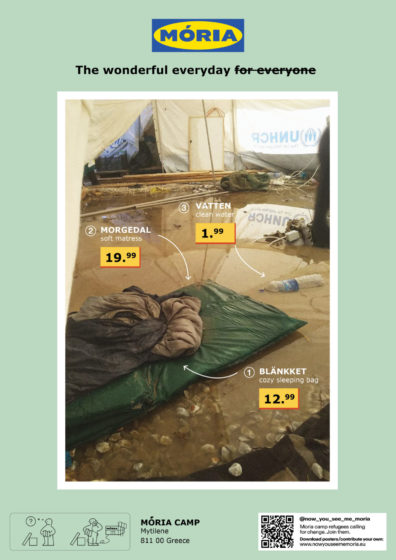

Now You See Me Moria, a collection of 446 campaign posters displayed alongside photographs taken by migrants inside Europe’s largest refugee camp, has attracted 33k followers on Instagram and exhibited across Europe. But the Amsterdammer who made it all happen wants only to be known as Naomí. ‘I try to erase myself as much as possible,’ explains the photographer (41) originally from Barcelona.

Inhuman

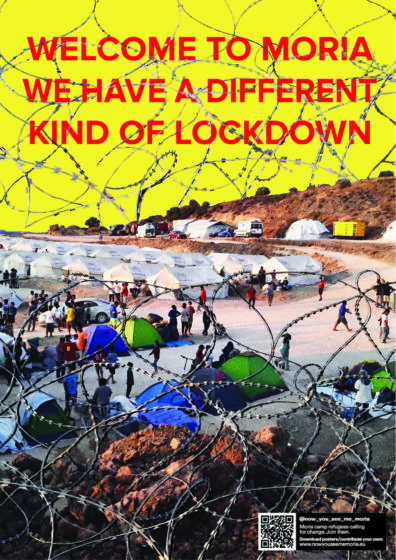

The growing team of photographers inside Moria are also simply known as Amir, Ali, Qutaeba, Mahdie and Mustafa – among others – since the precarity of their situation prevents them from giving their full names. Contained by concrete walls and barbed wire in a camp crammed to six times its capacity, a traumatised population of migrants, mostly from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq, can expect to spend an average of two years at Moria waiting for their asylum application to be processed and wondering what the future holds for them.

Until then, the only certainty is unsanitary accommodation, perpetual queuing (for food, water, clothing, documentation), and a feeling of being forgotten. Making residents wait for everything, says Naomí, is ‘done very consciously’. ‘You are giving them a very strong message: you are not welcome and you are not human like us,’ she says. Roughly a third of the 20,000 residents are children of school age. Their lack of education during their detention at the camp, say campaigners, contravenes their human rights.

Pain

Naomí, who fell in love with an Afghan refugee, has seen the impact of forced migration first hand. It was their separation in 2020 that triggered the campaign for Moria, where her partner was briefly based. When she stumbled on a photograph in her Facebook feed taken from inside the camp, a means of acting on her grief suggested itself. ‘I didn’t know what to do with that pain,’ she says. ‘And then I saw the photos of Amir.’

Since journalists are not permitted entry to the camp and NGO workers are not allowed to take photos, she got in touch with Amir and set up an Instagram account to share his images of life in the camp and to campaign for change. Just five weeks later, a fire destroyed the five-year-old settlement, and it’s equally grim replacement, Mavrovouni (often called Moria 2.0), was founded. Demonstrations at the time were widespread, but a silence swiftly resumed around the refugee crisis. ‘After the fire was gone, the media was gone,’ says Naomí.

Posters

As Moria’s refugees became invisible again, Naomí initiated a call to action, inviting designers to use the Instagram images − now augmented by numerous other residents − to make posters to petition the EU for change. 446 designs were produced by artists from 34 countries and the intitiative Love for Moria, on Valentine’s Day 2021, saw thousands of posters printed out and exhibited across Europe and beyond. As well as papering the walls of Foam, the posters have been compiled in a crowdfunded Action Book published by Paradox in a bound and unbound format which can be passed between friends to raise awareness or dismantled into posters demanding action.

Five months on and Naomí can barely keep up with the interest in the photographs and posters. Shows are normally planned many months in advance, but the Stedelijk are due to open their version of the exhibition in September and Naomí and the team are still working on the concept. Meanwhile, simultaneous exhibitions are currently running in Rotterdam, Austria and Germany. Next week, Naarden and Portugal will also give the campaign gallery space.

Collaboration

Normally competing for exclusives, with Now You See Me Moria, museums have taken the extraordinary step of showing the same exhibition, sometimes even in the same city. The approaches differ, however. Foam, for example, aims to increase the visibility of the Moria women, while the Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam tells a broader story of life in the camp.

‘It’s not about us. It’s not about egos. It’s about them,’ says Claartje van Dijk, who curated the exhibition at Foam. ‘For us, it really is a collaboration,’ she says. ‘We are all able to share one part of a bigger story. It’s so important together to be a louder speaker.’

Amateur

The amateur quality of the photos, mostly taken with smartphones, also breaks with convention, but gives the work an unexpected poignancy. ‘We are so used to perfection in photography,’ says Naomí. ‘You think, ‘wow, what a great photo’, … and then forget what is really happening in the image.’

There is ‘something poetic’ about Amir’s slightly blurred photos, she says. And Qutaeba, who took the campaign’s iconic image of narcissi growing from a bullet case, ‘really has an eye for photography’. In another of his pictures, a rainbow arcs over the makeshift shelters, inadequate against the extremes of the Greek climate.

Self-representation

Rather than a documentary maker looking from the outside in, the refugees’ photographs, says Naomí, offer ‘such a pure intention to show what’s happening’ and dispense with stereotypes. The exhibition hopes to undermine what Naomí describes as a ‘false discourse’ that refugees are dangerous and need containing with fences and walls, and instead show moments of daily life in the camp such as playing chess, cooking, or doing laundry. ‘Instead of focusing on what is different, it focuses on what we have in common,’ she says.

The exhibition also offers an alternative to the media’s depiction of asylum-seekers as a group, which can make it harder to empathise. ‘They are never individualised as a person with a name,’ explains Naomí. ‘We want to break the narrative and give them the chance to self-represent.’ Instead of images of victims, visitors will see portraits where women – in spite of all the adversity – try to look their best, and get to peek inside their tidy tents with their plumped pillows and neatly arranged shoes.

Visitors as messengers

The exhibition, and the campaign behind it, has three concrete objectives, which are spelt out on the museum walls: the immediate evacuation of the camps, the creation of new spaces for asylum procedures, and structural change to EU migration policies. Improving the camp is not one of the aims. Change can only take place if voters convince governments that it is important to them, Naomí explains, and she urges visitors to ‘be a messenger’.

Hidden from view in a gated hell just metres away from holiday-makers, Moria’s residents can finally share their truth. ‘We don’t just want to bring awareness … we want to engage people into action,’ Naomí says. ‘But first you have to be seen’.

Now You See Me runs from 2 July – 25 August at Foam Amsterdam and until mid-October at the Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam. The photographs can also be seen at the Foto Festival Naarden 3 July – 29 August and at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam from 21 September.

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation