Protestant church’s declaration of guilt towards the Jews is a historic step

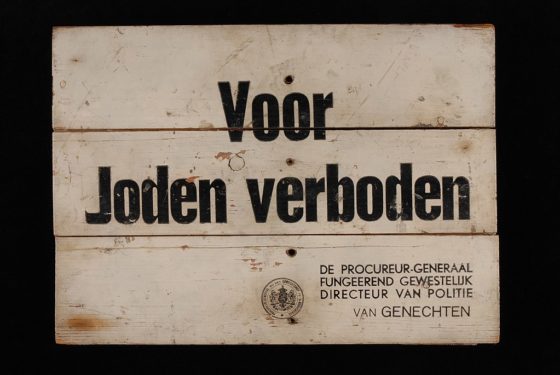

The Dutch Protestant Church is to admit that it helped to ‘sow the seeds’ of anti-Semitism and failed to protect the country’s Jewish population before, during and after the Second World War.

The Dutch Protestant Church is to admit that it helped to ‘sow the seeds’ of anti-Semitism and failed to protect the country’s Jewish population before, during and after the Second World War.

On Sunday, November 8, René de Reuver, the church’s official scribe, will read out a ‘declaration of guilt’ in the Rav Aron Schuster Synagogue in Amsterdam as part of the commemoration of Kristallnacht, the ‘night of broken glass’ in 1938 seen as the moment when the Nazis’ oppression of the Jews tipped over into outright persecution.

‘We fell short in our words and in our silence, in our deeds and our inaction, in our attitude and our thoughts,’ Reuver will say. ‘The Protestant Church in the Netherlands wishes to acknowledge without reservation that the church prepared the fertile ground in which the seed of anti-Semitism was able to grow.’

The acknowledgment of the church’s contribution to the suffering of the Jews is the latest stage in the Netherlands’ long reconciliation with its wartime past. In January 2020, on the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, the prime minister, Mark Rutte, formally apologised for the behaviour of government officials during the occupation. ‘Certainly there was resistance within government by individuals, but too many Dutch functionaries carried out what the occupiers demanded of them,’ he said.

King Willem-Alexander tackled the same theme at the annual commemoration of the war dead on May 4, when he told an eerily deserted Dam Square that his great-grandmother, Queen Wilhelmina, largely ignored the plight of the Jews during her radio broadcasts from exile in London. ‘Fellow citizens in need felt insufficiently heard, insufficiently supported, even if it were only with words,’ he said. ‘Even from London, by my great-grandmother, as tenacious and strong as she was in her resistance. It is something that will not leave me.’

The Protestant church’s declaration followed months of dialogue with the Jewish community that began with Rutte’s apology. Eddo Verdoner, chairman of the Jewish liaison council CJO, says: ‘It’s not something we’ve been asking for for decades and it may come to outsiders a little bit out of the blue. But when it happened we were very happy that that step was finally being taken, even though it has come very late.’

Guilt not apologies

The Church’s decision to express its regrets in terms of ‘guilt’ rather than ‘apologies’ is in keeping with Christian doctrine that regards sin as integral to human nature and requires people to ask forgiveness from God. ‘Guilt is the deepest word you can use for your failings,’ De Reuver told Trouw newspaper. ‘We are not distancing ourselves from the past, but taking responsibility and recognising our mistakes.’

Verdoner respects the Church’s choice of language. ‘It’s really a matter of semantics,’ he says. ‘I think the fact that they came as far as doing this, even though they knew they would get some backlash from it, is very brave.’

De Reuver accepted that for some people, the Church’s admission of responsibility has come too late – a charge that was also levelled at Rutte, whose statement was the culmination of decades of debate.

Wim Kok’s cabinet in 2000 apologised for the ‘cold reception’ of many Jewish survivors who returned to find their homes reoccupied and no acknowledgment of the trauma they experienced. Kok set up a compensation fund worth 680 million guilders (€310 million) for victims of the war, including 400 million guilders for the Jewish community.

The chequered history of the German occupation have made reconciliation a long and fraught process. Thousands of Jews arrived from Germany in the 1930s, believing that if war broke out the Dutch would remain neutral, as they had in World War One. In the wake of Kristallnacht the government stepped up border controls and applied a refugee strict quota, accommodating a maximum of 2,000 children.

After the Germans invaded in 1940 the police took control of the camps the Dutch had set up to house illegal migrants and turned them into transit camps, from which nearly 100,000 people were deported to Auschwitz and Sobibor. Ultimately around 75% of the pre-war Jewish population was murdered by the Nazis.

Church and conscience

Organised resistance emerged relatively slowly compared to countries such as France and Belgium, but around 30,000 Jews survived the war either by going into hiding or being smuggled out of the country. Perversely, that experience complicated the issue of seeking redress from the government and the Church, says Verdoner.

‘A lot of people in the community today were saved during the war and very often that was by somebody from the Protestant Church or somebody who was asked by a person from the Protestant Church to help the Jews. But there’s also a bias there, because only the people who survived are able to speak. The largest part, those who didn’t survive, cannot speak. And that is something we must always remember.’

That dilemma of choosing between church and conscience is still relevant in today’s more secular society, he says. ‘The Protestant church, or a certain part of the church, had this view that whoever was in power was put there by God and therefore should be respected. That’s a good lesson for the future, because it shows that even today, if you see a leader or a government singling out people for no reason and driving them into a corner, you should not follow blindly.’

Arnon Grunberg

The Dutch-Jewish writer Arnon Grunberg drew parallels between the treatment of the Jews in the 1930s and the hostility faced by minority groups today in his May 4 address this year when he said: ‘When they talk about Moroccans, they talk about me.’ It prompted outraged responses on social media, leading Grunberg to clarify that he was not making a direct comparison between Jews and Moroccans, but speaking out against prejudice in general. ‘When a group in society is marked as a scapegoat, I feel we have a duty to show solidarity with that group,’ he told NPO Radio 1.

Verdoner says Grunberg was right to apply the lessons of the 1930s to today’s politics. ‘Are Muslims today in the same category as Jews were then? Categorically not. But I see that the populism and the polarisation we saw in the 1930s has been let back into our lives a little bit and I think we should fight with all our might to put that spirit back in its cage.

‘That’s what Arnon Grunberg tried to do. He tried to say: listen, it’s bad if we generalise, it’s bad if we say a certain group is to blame for the problems we have. That is wrong and it’s being used by people to set us up against each other. And we know from history that it can do a lot of damage.’

That is what makes the Protestant church’s declaration of guilt, even 75 years after the event, an important milestone, says Verdoner: it helps to ensure the lessons of the war stay relevant for future generations. ‘Even today you shouldn’t underestimate the power of the church. People may not go to church as often, but in our education, the way children are taught at home, thoughts and lessons are passed on from generation to generation.

‘The fact that it’s news when we talk about anti-Semitism and it’s not something we take for granted or just accept means that we have the right set of values in our society.’

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation