WWII bomber recovery in the Markermeer lake ends 12 year mystery

On a winter’s day just before Christmas in 2008, the Royal Dutch Rescue Society received a call-out to a boat that had broken down on the Markermeer lake, around six miles north-east of Amsterdam.

The crew dropped anchor while they waited to be rescued, and when they pulled the weight back up again they found a piece of aircraft machinery attached. It was the first piece of a wartime puzzle that would take 12 years to piece together.

More than 3,000 Allied planes were shot down over the Netherlands during World War II. They came to rest in fields, skewered through farm buildings, in the North Sea or in the country’s network of waterways.

Thirty years after the war, a teenage boy named Johan Graas began poking around crash sites with his metal detector. ‘I was at a birthday party where an uncle of mine was telling me how he had found a lifejacket at a crash site,’ he recalls. ‘An American life jacket with a name on it. As a 16-year-old boy I found it fascinating, so I went out to the site, just outside Purmerend, and asked the landowner if he knew about the crash. And he showed me the spot. At a crash site you get lots of oil and fuel seeping into the ground. The vegetation is different: it’s discoloured and there are a lot more weeds.’

Metal detector

‘So I bought a metal detector and started digging, and 10cm beneath the ground we found the first pieces. It was an American B24 Liberator – most of it had already been recovered, but we found a propellor, a ball turret and machine-guns. The aircraft pieces were interesting, but I started wondering: what sort of people flew these planes? How young were they? I became fascinated by these guys of around 20 or 25, sometimes 30. They had families, they had hobbies, they’d been through school and graduated and I thought: what made them volunteer to give it all up for this?’

Graas’s curiosity became a lifelong quest to retrieve the relics of war. At weekends he would go out scouting fields or diving in the IJsselmeer – the lake formed with the Markermeer after the damming of the ZuiderZee – chasing tip-offs about newly discovered crash sites.

‘I had a busy job and I was doing this for 30 to 40 hours a week. I was never home,’ he says. When people found pieces of plane wreckage while out walking or fishing, they took them to Graas.

In 1987 he founded the Stichting Aircraft Recovery Group, a volunteer organisation with around 35 members dedicated to identifying lost wartime aircraft and – crucially – tracking down the relatives of the lost airmen. A selection of the group’s finds is on display in its museum at Fort bij Veldhuis, a giant converted bunker off the A9 at Heemskerk.

Aluminium panel

The fishermen who hauled the wreckage from the bed of the Markermeer at Christmas 2008 contacted Graas, who immediately identified it as a motor from the landing gear of a Short Stirling bomber.

‘When you’ve been doing this for 45 years you recognise just about every part of every plane,’ he says. The Short Stirling was a four-engined plane used by the RAF on bombing raids between 1941 and 1943, when it was superseded by the more versatile Halifax and Lancaster bombers.

Graas set his team of divers to work and within a few days recovered further pieces, including an aluminium panel with the plane’s serial number on it. Years of lying in the mud had faded the paintwork, so Graas sent it for analysis to the police forensic investigation unit at Schiphol, where it was identified as the Short Stirling BK710.

‘We suspected it was likely to be the BK710 and they confirmed it, so I didn’t investigate further,’ says Graas. ‘They were a professional organisation so I assumed they’d get it right.’

The next stage was to contact the relatives of the deceased airmen using the tools of the amateur detective’s trade: a list of the crew from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and a telephone directory.

‘All I had was their surnames and the place they were born. So I’d send hundreds of letters to everyone with the same name in their home town and wait for the replies.’ In the case of the BK710 Graas estimates he sent 450 letters over the course of four years. The responses came in from all corners of the Commonwealth: relatives of missing airmen from the same plane often stayed in touch after the war, and Graas’s letters were distributed through these networks.

Shot down

The BK710 had been shot down on the night of May 25, 1943, over the North Sea on its way back from a raid over Düsseldorf. The operation, involving 759 aircraft, was not judged a success – only between 50 and 100 buildings were destroyed, as a combination of bad visibility and decoy fires lit by the Germans threw the bombers off course.

The toll on the RAF was high, with 27 aircraft lost and 161 crew killed. The BK710 was on its way back to RAF Lakenheath when it was hit 40 miles north-west of the island of Texel. Most of the seven crewmen were heading back for a few days’ leave; wives and girlfriends had congregated under the clock at Waterloo Station in London, ready to greet them.

Rear gunner Charles Percival baled out, but landed in the sea and was washed up on the German island of Heligoland. The others were presumed to have perished in the plane. Though the flight path of the BK710 was to the north of Amsterdam, the 21-year-old pilot, Jack Henry Uden, appeared to have turned inland and ditched in the Markermeer as he tried to find a spot for an emergency landing.

The divers’ efforts revealed that the remains of the bomber were strewn over a large area, indicating it was still moving forwards as it hit the water. They also found three parachute locks with the clasps still fastened, a sure sign that the men had not had time to jump out of the plane. Their remains were therefore still in the water.

Even 75 years on, the discovery of a ‘missing’ airman’s last resting place is an emotionally charged event for his family, says Graas. ‘It’s better to know that someone’s been found dead than that they’re missing. That’s the worst thing you can hear.’

Relatives expect that the bodies, or whatever remains of them, will be recovered and given a proper burial. But their hopes often foundered on the rocks of Dutch regulation. Until recently, the state would only cover 70% of the cost of recovering an aircraft, with local government liable for the balance.

Councils were reluctant to find the funding, especially for something as costly and complex as recovering an aircraft from the water. ‘Some councils would do it, others wouldn’t, but the municipalities that covered part of the IJsselmeer tended to say, they’re fine where they are,’ says Graas.

There were also issues around the legal status of wreckage sites. ‘The defence ministry sent round a circular on aircraft recovery which described them as war graves,’ says Graas. ‘But that’s not legally correct. I asked two independent legal experts to look into it, and they both concluded that they’re not war graves: they’re places where a fatal accident took place. That’s a very different thing.’

Petition

The families of the BK710 crew spent years petitioning to recover the wreckage from the water. Letters were sent to Almere council, government ministers in the UK and the Netherlands, Dutch members of parliament and even prince Charles. ‘This is not the end of the story,’ Margaret Hadden, the sister-in-law of flight engineer Leslie George Hadden, told EenVandaag in 2018. ‘George has to be recovered and given a decent burial. If they don’t bring the plane up it’s like losing George again.’

In November 2011 a memorial was unveiled on the island of Marken, composed of a propellor blade on a stainless steel plinth and the names of the seven crewmen. The deadlock was broken in 2018, when the government agreed to pay in full for the recovery of between 30 and 50 aircraft over the next 10 years at a total cost of €15 million. One of the first wrecks on the list was the Short Stirling at the bottom of the Markermeer.

In the meantime, Graas’s team had recovered further artefacts that were causing alarm bells to ring. One was a cigarette case engraved with the initials JMC, which did not match any of the crew of the BK710. Another was a wooden elephant that appeared to be the squadron’s mascot. But the BK710 belonged to No. 149 Squadron, whose emblem was a horseshoe and a lightning bolt.

Graas began a new search and soon discovered that another Short Stirling had been shot down on March 30, 1943, around 4km east of Marken island. The aircraft belonged to No. 218 ‘Gold Coast’ Squadron, based at RAF Downham Market, which had been officially adopted by the governor of Gold Coast, the colonial name of Ghana. And among the seven airmen who flew on that fatal mission was a John Michael Campbell – JMC. The plane’s serial number was BK716.

In the museum, Graas points out the aluminium panel with its three-digit number almost stripped away after decades in the water. ‘Here you can see a complete grey 7, this is a grey 1, and this is what we thought at first was a zero. But if you look really closely you can see it stops here and turns very slightly inwards.’

It was a heart-stopping moment. ‘I’d done hundreds of investigations and never been wrong, but the one time I call in an official agency I get a bum steer,’ says Graas. As well as a new search for the relatives of the BK716, he now faced the unenviable task of telling the families of the BK710 crew that the plane they had spent 10 years campaigning to retrieve from the water was, in fact, a different aircraft.

‘I sent them an email first of all, telling them I had disappointing news,’ Graas explains. ‘But then I realised it’s not the sort of thing you can reveal in a phone call or an app chat. So in May last year [2019], once we knew for sure it was the BK716, I went to England and spent a week visiting as many of the relatives as I could. It wasn’t a nice job: the news was shocking for them. But their responses weren’t as bad as I expected. They said: you can’t change history and other families will be glad that the BK716 has been found.’

All seven crew of the BK716 are believed to have been on board when it hit the water on the night of March 29, 1943, as it returned from a sortie over Berlin. They included five British airmen and two members of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Determination

One of them was the 24-year-old navigator, Harry Farrington, from Niagara Falls, Ontario. He had qualified as a banker and was working as a clerk at the Canadian Bank of Commerce, but when war broke out he volunteered to train as a pilot – rejecting the offer of a more secure role as a radio mechanic. Harry’s father, Arnold, had died when he was 19 and his younger brother, Clifford, succumbed to diabetes as a child, leaving his mother, Bertha, alone with his sister, Edith.

Now 94, and still living in Niagara Falls, Edith McLeod recalls how determined her brother was to go to the front. ‘His bank manager told him he did not have to go because my mother was a widow and I was the only one left,’ she says in a video call from Canada. ‘His bank manager tried very hard to convince him not to sign up, but Harry felt it was his duty. And my mother said: if that’s how he feels, that’s fine. So he joined up.’

‘He was very good to me after my father died,’ says Edith, who was eight years younger than Harry. ‘We were interested in the same things. We both played basketball: he was a good player and he came to see my games when he could.

‘I was singing in a musical festival in Niagara Falls one time and mother left him a note saying that’s where we’d be if he got home. So he came up and walked in the gym just as I was about to sing and it was a lovely feeling. We were close.’

Harry’s dreams of becoming a pilot were dashed when his examiners rated his flying skills ‘below average’ and ‘extremely poor on landings’. Instead he was given the job of navigator with 218 Squadron. In England he met Kathleen Blease, who had survived a Blitz strike on her block of flats in London not long before, and married her in January 1943. They were allowed two days’ honeymoon before he returned to service.

Wedding

‘I wish you and Mother could have been here for the wedding (we’d have had you sing) but it just wasn’t possible,’ he wrote to Edith in mid-January. More letters followed, the last on March 14, when he confided he had ‘been over Germany quite a few times and dropped a few bombs for you’. He went on: ‘Our crew are as pleased as Punch because we’re getting a brand new aeroplane when we come back from leave – it’s going to have a green dragon painted on it and we’re calling her The Dragon’s Revenge – like that?’

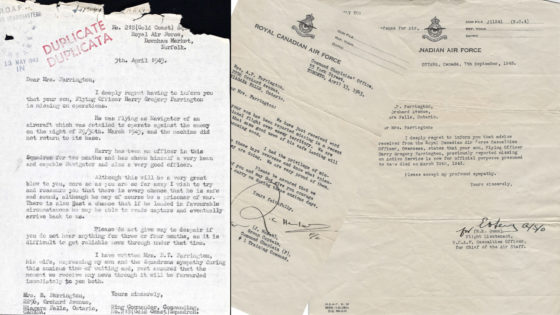

Less than two weeks later, Harry was reported ‘missing in action’. ‘I’d just gone out when the telegram came,’ recalls Edith. ‘I’d gone to fetch a bottle of ink for school. That was it. I remember how badly I felt because mother was alone.’ A typed letter from his commanding officer followed, explaining that Harry was ‘missing on operations’ and may have been killed or taken prisoner of war.

More letters and telegrams followed in the coming months, in which the hope of Harry returning home alive steadily receded. But officially he remained ‘missing’, even after the terse letter of September 7 stating he was ‘now for official purposes presumed to have died on March 29, 1943’.

That Harry’s last resting place now appears to have been identified, nearly 80 years on, is ‘very special,’ says Edith. ‘My mother’s at peace, even though she’s died. She knows all that happened now, and so do I.’

Recovery

The operation to recover the Short Stirling begins on August 31 and is expected to last five to six weeks. It is a complex collaboration involving researchers, army and air force technicians, and civilian recovery specialists. Because of the aircraft’s recent history, the military is still hedging its bets as to whether the pieces belong to the BK716.

‘For us it’s the most likely candidate,’ says Major Bart Aalberts, aircraft recovery staff officer for the Royal Netherlands Air Force. ‘The best thing, and what we’re hoping for, would be to find one of engines with the serial number engraved. Than we can say with certainty: that’s the aircraft.’

The engineers will sift an area of around 75 metres squared with diggers and analyse everything larger than 8 millimeters, so any machinery parts or human remains can be identified. The technique has provoked some controversy, but Major Aalberts says it was the only viable option for such a large area.

The alternative method of building a dam around the crash site and draining it was used four years ago to recover a Wellington bomber, but its remains were confined to a smaller area of around 34 by 23 metres. ‘The image people have in their heads is of a complete wreckage of a plane with the bodies still inside, but that’s not the reality,’ Major Aalberts says. ‘In this case the aircraft hit the water with such great force that it was spread across a huge area.

‘The lake bed mainly comprises sludge. The small, fine pieces only become visible on the sieve, regardless of whether the sludge is dug up wet or dry. And we don’t know beforehand where we’re going to find machine parts or human remains. The Aircraft Recovery Group has found the parachute locks, so we know that the bodies were in the water. But are they still there?’

Major Aalberts welcomes the government’s decision to fund more operations, but says it is ultimately down to municipalities to decide whether wrecks are recovered. ‘The awkward truth is that more than 250,000 servicemen from Britain alone went missing over Europe during the two world wars,’ he says. ‘We’ll never find them all. But it is far more interesting and satisfying for us when we’re able to bring a missing airman home.’

For more information about the Aircraft Recovery Group and museum, visit www.arg1940-1945.nl

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation