The erotic Dutch surrealist you should have heard of

A new exhibition at the Utrecht Centraal Museum explores themes of gender, misogyny and sexuality in the work of Dutch artist Jaap Moesman and puts a spotlight on the contribution of female surrealists.

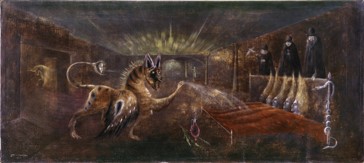

From mystifying, mirage-like landscapes to bondage and necrophiliac mice – a host of subliminal fantasies and fears come together in one extraordinary art exhibition, ‘The Tears of Eros: Moesman, Surrealism and the Sexes’, which opened on Saturday 15th February at Utrecht Centraal Museum.

Spanning four huge rooms, an annexe, and various spaces in between, the 264 works on show include surrealist royalty such as Salvador Dali, René Magritte and Man Ray, and contemporary artists inspired by the movement such as Dutch photographer Viviane Sassen and British sculptor Sarah Lucas.

Freeing the subconscious

Surrealism, meaning beyond realism, sought to convey a subliminal ‘super-reality’ previously unarticulated. The manifesto of surrealism, written in 1924 by French poet and writer André Breton, marks the clearest start to the surrealist period which slowed with the end of the Second World War. Proposing a new method of artistic creation, the manifesto asked for ‘pure psychic automatism’ and ‘the absence of any control exercised by reason’, since a rational mind was believed to inhibit expression.

As fascism and war cast a shadow over Europe, this freeing up of the subconscious and exploration of repressed desires had a rebellious, debauched quality to it. Surrealism is often described as ‘a little bit of a weird, dreamy world’, says the exhibition’s curator Nina Folkersma. ‘Actually, it was a very political movement.’ The focus on sex and erotics, she explains, ‘was a liberating force for them’.

Who was Moesman?

The Tears of Eros is part of Utrecht’s Moes Mania, a programme of events (6 January – 24 May) celebrating the work of Jaap (Johannes) Moesman (1909-1988), who was born in Utrecht. Moesman worked as a lithographic draughtsman for the railways until the 1960s, a trade he had learnt from his father, a collector of curiosities, who shared his interest in art and the exotic. Both were involved with the art society Kunstliefde, which still exists today, and Moesman took life drawing lessons. It was ‘Nord’, an art gallery and bookshop in the Vinkenburgstraat, run by the surrealist artist Willem Wagenaar, which would introduce him to the surrealist movement in the late 1920s and set him on a new creative path.

In 1961, Moesman was finally acknowledged by Breton as a surrealist of significance when his work was selected for the International Surrealist exhibition in Milan. But censorship of his work – deemed obscene – was a challenge throughout his life and his difficult personality meant his relationship with galleries was often fraught.

Putting Moesman on the map

An exhibition marking the centenary of the surrealist manifesto is due to take place at London’s Tate Modern in 2024, and it is hoped that by showcasing Moesman alongside fellow surrealists, the Tears of Eros will help earn him a place in this prestigious show.

But altering preconceptions is never easy. ‘Most often, art history is written out of the power centre of a certain movement – Paris with André Breton was very much at the centre of that,’ explains Bart Rutten, Centraal Museum’s artistic director.

‘What I like is that we are, in this globalised world, also breaking up those power centres and starting to look carefully at what could have been more interesting in earlier days that was overlooked by the most influential writers … That is a kind of hidden strategy for this exhibition – that we can really fuel the oeuvre of Moesman and put him more in the spotlight, also for international colleagues.’

Misogyny

This exhibition is also refiguring power centres by questioning the gender bias within surrealism, a movement which both reinforced and undermined the status quo. Revolution and liberation were central to surrealism, but not at the expense of the patriarchy, and women are mostly fetishised and objectified in the works on display.

Depicted as a faceless body, tied up, mutilated or deformed, these erotic works reveal a great deal about prevailing attitudes to women and the psyche of their predominantly male painters. Breton’s manifesto called for an art that is ‘beyond any aesthetic or moral preoccupation’, and this is reflected in the violent, self-gratifying quality of some of the works, particularly towards the end of the exhibition where the influence of sadomasochism is explored.

The work of female surrealists offers an alternative perspective on gender and sexuality, with many artists self-depicting as aggressive and powerful, rather than submissive. Belgian artist Sanam Khatibi (1977), for example, portrays women as blood-thirsty hunters, while Argentinian-Italian artist Lionor Fini (1907-1996) depicts them as proud warriors and predatory sphinxes.

New perspectives

‘If you look at the works there, it’s a completely different aesthetics; it’s a completely different layer that they’re adding,’ says Folkersma, who expects some visitors to be surprised that some of the women’s contributions look unlike what we normally associate with surrealism. ‘That’s the whole point,’ she says. ‘We need to extend our idea [of surrealism].’

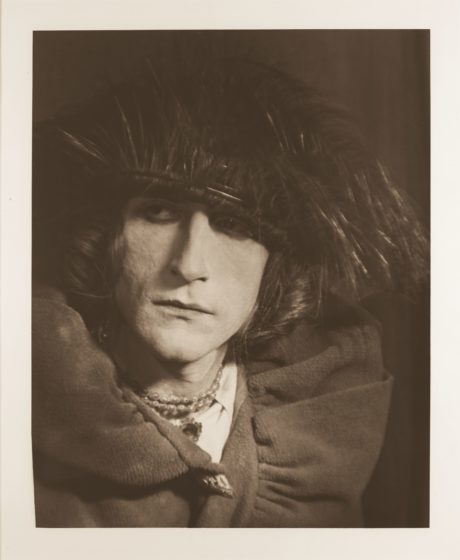

Many works in the exhibition reject gender binarism and question pervasive ideas of gender identity. ‘Me as Madame and Monsieur Duchamp’ (2018), a bromide print by Turner Prize winner Gillian Wearing (1963), for example, sees the artist dressed as both male and female characters. Wearing was influenced by the androgynous self-portraits of French artist Claude Cahun (1894-1954) (born Lucy Schwob), whose works also hang in the gallery. Elsewhere, cross-dressing is eroticised, such as in the silver gelatine prints of French artist Pierre Molinier (1900-1976), a transvestite fond of women’s lingerie, who made himself the subject of many of his works.

Challenges

The exhibition begins with a video reconstructing a 1928 meeting of male surrealists, sipping drinks and pontificating on their own sexuality, with no reference to the experience of women. But by the end of the Tears of Eros, it becomes clear that surrealism is no longer to be seen as a boys’ club. In fact, the greatest challenge in pulling this extraordinary exhibition together was the competition for works by female surrealists.

‘While they have been ignored for a very long time, now there’s a lot of attention on them and shows everywhere,’ says Folkersma, who was dismayed to discover that Fantastic Women, an exhibition of female surrealists, was opening In Frankfurt on the very same day as the Tears of Eros.

Now that the works she fought for are hanging in the Centraal Museum’s gallery, Folkersma sees the demand for surrealist pieces by female artists as a positive sign. ‘It is the moment for women in art now,’ she says. ‘We were there all along. We just didn’t appear in the books.’

The Tears of Eros: Moesman, Surrealism and the Sexes runs from February 15 – May 24 at the Centraal Museum Utrecht.

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation