In the lion’s den: resistance and propaganda in a museum at war

Senay Boztas

The 13-year-old boy would take the copies of Trouw carefully typed by his father and tuck them under his shirt. Then from his home, right under the noses of the Nazi occupiers, he would cycle the resistance newsheet around The Hague.

This was 1944 at the Mauritshuis museum, when museum staff were walking a dangerous tightrope between resistance and placating the Nazi command around the corner. Mense de Groot, administrator and resistance activist, had moved into the basement of the museum with his wife and children including that boy, Menno.

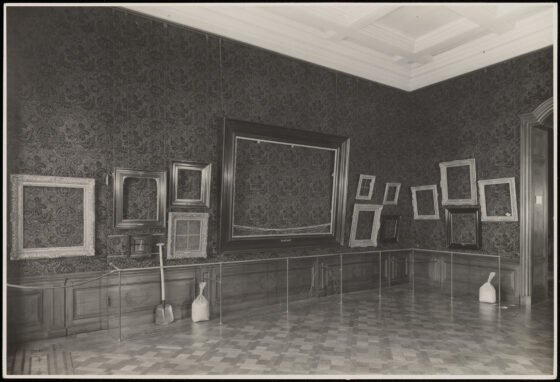

The most important paintings had been carefully hidden. And as the Nazis called up thousands of Dutchmen for Arbeitseinsatz forced labour conscription, the attic of the Mauritshuis housed an unknown number of men in hiding.

Now, an extraordinary exhibition at the Mauritshuis, Facing the Storm, and an accompanying book recount the secret history of this Dutch museum in World War II. “I remember one time, there was a guy, he used the bell,” Menno, now 93 and living in Canada, says in a film in the exhibition.

“I opened the door and he said to me: ‘Tell your dad I’m here’. I tell myself: ‘Who are you?’ He put his bike somewhere and went upstairs. Where he went I don’t know. He must have gone all the way to the attic. I don’t know how many there were up there, I have no idea how they lived up there, how they got there.”

Recounting his memories of the war time – when he lived in this building for more than two years – De Groot tells his granddaughter Kella Flach more than once: “You had to be very careful.”

Hiding in plain sight

This was of course quite an understatement, explains curator and researcher Quentin Buvelot: it was hugely risky to deliver a resistance newspaper or shelter people in hiding. The seeds of the exhibition were sown when father Mense de Groot’s logbook including that time turned up in a Mauritshuis archive. And the biggest surprise to modern-day researchers was the discovery that people were at one stage hiding in the attic.

“They were hiding in the Mauritshuis but that means hiding in plain sight,” he tells Dutch News. “We know they were there, but we don’t know how many there were. And also, was it just for a week or longer? We don’t know.”

A research team including specialists from the NIOD institute for War, Holocaust & Genocide Studies found that the German-born museum director Wilhelm Martin had made a subtle reference to these people in a short document written before he retired. “The director writes that there were two locations with people hiding, the Mauritshuis and another location in The Hague, not far from the museum, and that there are 36 [daily] loaves of bread that are divided between the two locations,” says Buvelot.

Frank van Vree, researcher at the NIOD and professor of the history of war, conflict and memory at Amsterdam University, says there are more clues to this time in a farewell speech for the director given by father De Groot.

The speech went: “And it was precisely during that time that we learned to appreciate you so much: people came closer to each other because of the circumstances, and I would like to tell you now that during the razzia days in winter 44/45, when more than one person was hiding in this building, we had such a peaceful feeling when you were in the building and as soon as you left again we felt like children who no longer had a father.”

Van Vree has found that the Mauritshuis was not the only museum to serve as a refuge during the occupation. “We know, for example that five people [were] hiding in the Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie in Leiden. And hiding in Museum Mesdag in The Hague was Henk Bremmer, a professor of physics, employed by Philips and namesake of a mathematical method, the Bremmer series,” he explains.

Another discovery was that father De Groot – clearly a resistance figure – organised evening concerts for out-of-work artists who refused to work for the Nazis. “There were clandestine concerts organised by that family living in the apartment under the museum, but being in the lion’s den, it’s difficult to go into the museum unseen and leave it unseen,” says Buvelot. “If they had found Menno delivering these copies of Trouw, he would have been punished. Only when he became older does he realise how dangerous it actually was.”

Smuggled on the train

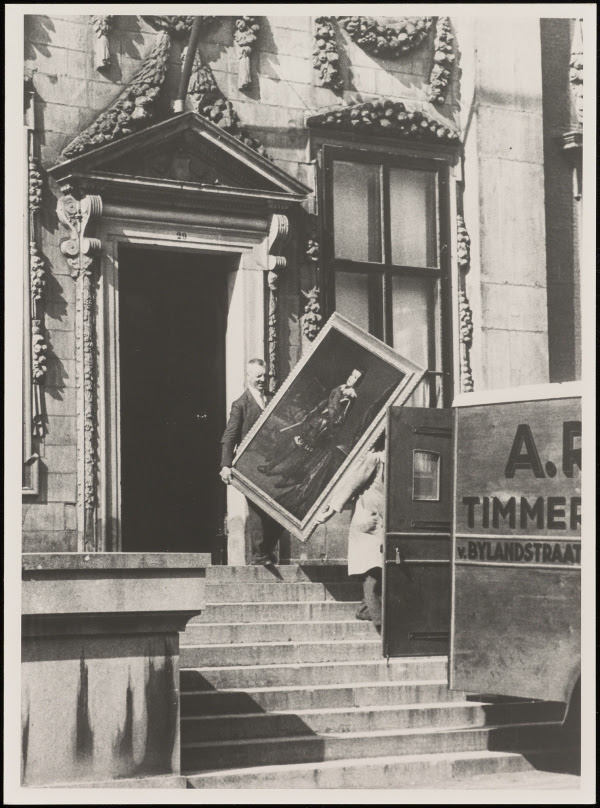

The exhibition and book also reveal the extraordinary efforts to save the best art in the Mauritshuis from the Nazis. Works were categorised according to a red/white/blue triangle scheme on their backs according to their importance; at one stage, the director even took Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring on the train with him down to a hiding place in Maastricht.

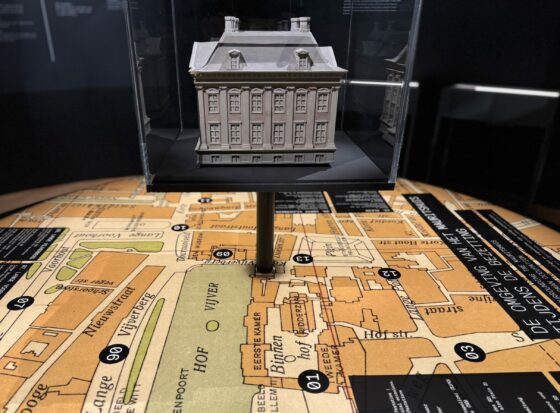

“When it comes to art protection, the Mauritshuis occupied a rather unique place among Dutch museums,” explains Van Vree. “It was the only museum that already had its own reinforced bunker under the building at the time of the German invasion.”

Before this exhibition, little was actually known about how people in municipal jobs such as running museums operated during the war. “In the Netherlands, but maybe also in other countries, culture could be a political instrument for resistance from the Netherlands on the one hand, but also a strong political, ideological instrument for the occupier,” says Eelke Muller, historian and NIOD specialist in looted art.

Dilemmas

“Every civil servant in times of war was confronted with huge dilemmas. And this museum had a special place, right in the lion’s den, in the middle of the power centre of the Germans where every day you would see them marching and the Nazi flags.”

During the war, the museum ran five propaganda exhibitions for the Nazis, which are partially on display again in the current show. But the exhibition and book argue that viewing people as either resistors or collaborators during this time is too simplistic.

What matters is openness, says Raymund Schütz, historian and researcher at The Hague city archives. He believes that oral accounts like Menno’s are hugely important but that archives should now be fully open too.

“It’s really very difficult to understand the contextual factors that made people do what they did in the end,” he says. “But the best thing is really to be very transparent and to make sure that all the information is available. And there has been a lot of silence during the past 80 years.”

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation