New legislation will open WWII collaboration archive: minister

Molly Quell

Education and culture minister Eppo Bruins is preparing new legislation which will open controversial digital archives on possible collaborators during World War II to the general public, he told current affairs programme Buitenhof at the weekend.

The archives should have been fully online from January 1, but that plan was halted because of privacy concerns. Instead, only the list of names of suspects was made available – even though many were never investigated.

The records from the Centraal Archief Bijzondere Rechtspleging, or Central Archives for Special Jurisdiction, include some 425,000 names of people suspected of having helped the Germans and are a “reflection of a chaotic period”, after the war, Bruins said.

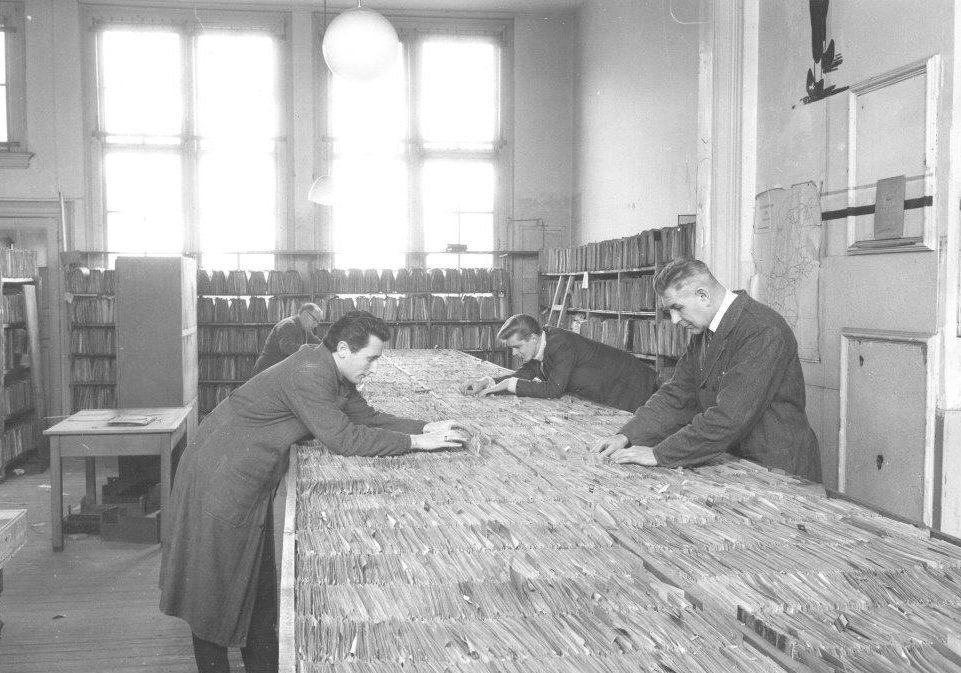

The project to digitalise the files had taken five years and was hotly anticipated by researchers and family members keen to establish the truth about their relatives.

But many were worried about what secrets the archives had and what impact revealing that information would have on those alive today.

Data privacy

The opening of the archive was done with the input of a wide range of organizations. Stichting Werkgroep Herkenning, which represents the relatives of collaborators, participated in the process, as did NIOD, the Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies and others.

In May 2024, however, the privacy watchdog Autoriteit Persoonsgevens became involved after someone submitted a complaint that the archive might violate European privacy laws.

The EU regulation protects sensitive information of anyone living and, while many of those investigated have since died, their relatives mentioned in the files may not be.

The archive conducted multiple expert analysis, including in consultation with the AP, which all concluded making all of the documents publicly available would run afoul of data privacy rules.

The National Archive moved forward with its plans anyway until a formal warning from the AP late last year spurred Bruins to halt the process. The minister said at the time he was disappointed at the delay because of the “great social importance in making this archive fully open and accessible”. Instead, only the list of names would be placed online.

Compromise

To view the corresponding dossiers requires an in person visit to the archives in The Hague – a situation which is the same for all historical archives. Only relatives or someone with a demonstrable personal interest can make an appointment.

But many people are unhappy.

“The publication of the list of names has caused great social unrest. Although the list only contains names of persons who are demonstrably dead, this does not detract from the impact on family members and those involved,” the NIOD said in a statement. The organisation has called for the archives to be open fully.

Archivists are also worried about the implications of the decision. “We fear that this will have catastrophic consequences for researchers and citizens seeking evidence, because now there is a threat that archive institutions will feel compelled to close all war-related archives in the Netherlands,” the Dutch archivists’ association said in a statement.

Flooded with requests

On the day the archive opened, the website had 300,000 visitors. The limited spots in the archive’s reading room quickly filled up. There is now nearly a two month waiting list for an appointment.

“When I saw my father’s name, I was shocked,” Peter Baas told The Associated Press. His father, or so he thought, was a decorated resistance fighter. Baas lives in France, so traveling to The Hague is challenging. “This is a very complicated way to get your family history,” he said.

Historian Karin van Coevorden told the Telegraaf that she had found names of her family members who should not have been included and suggested that witnesses may have ended up being listed as suspects. The names of 25,000 people have since been deleted.

Largest archive

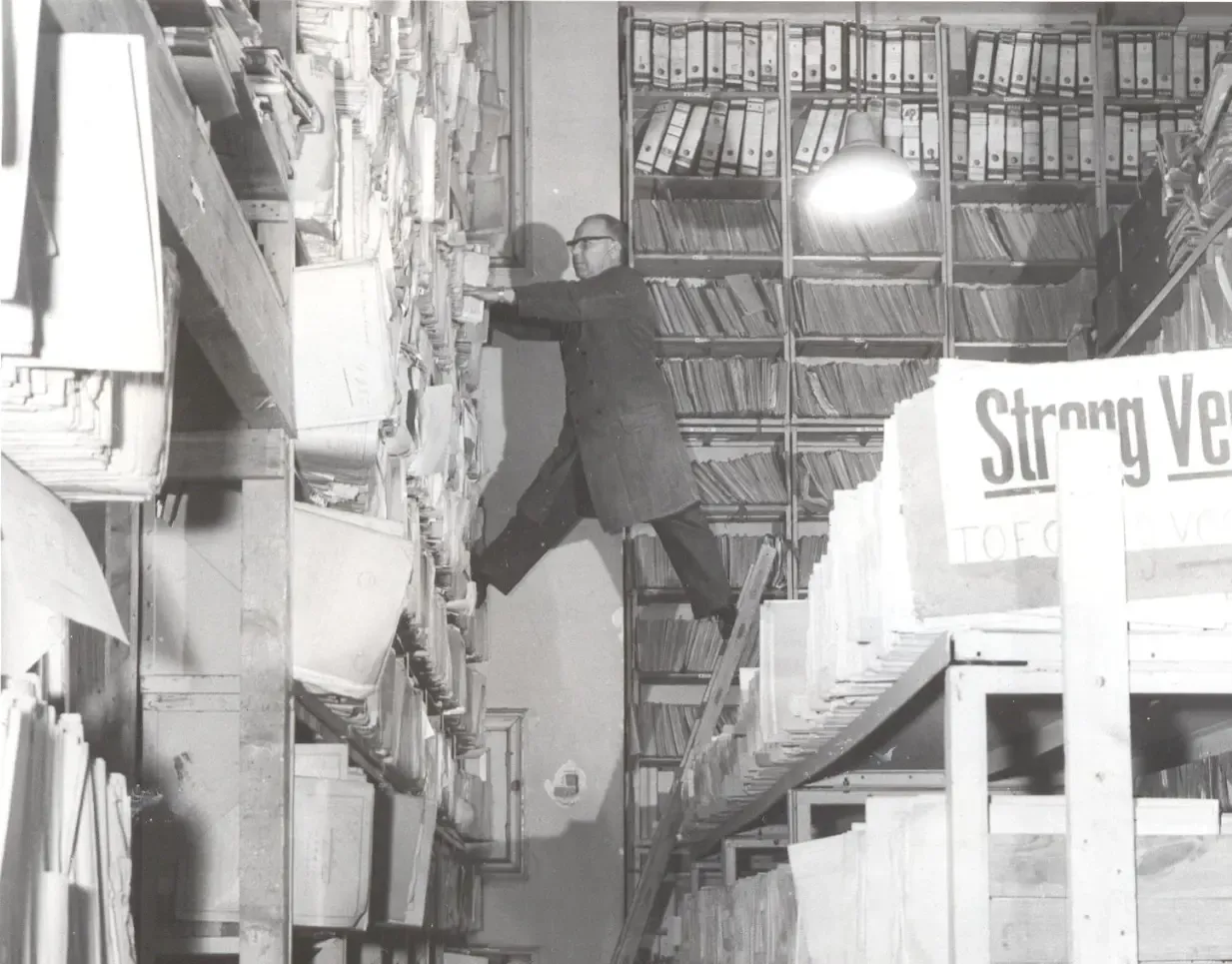

Stretching nearly 4 kilometers, the CBAR documents are the largest WWII archive in the Netherlands.

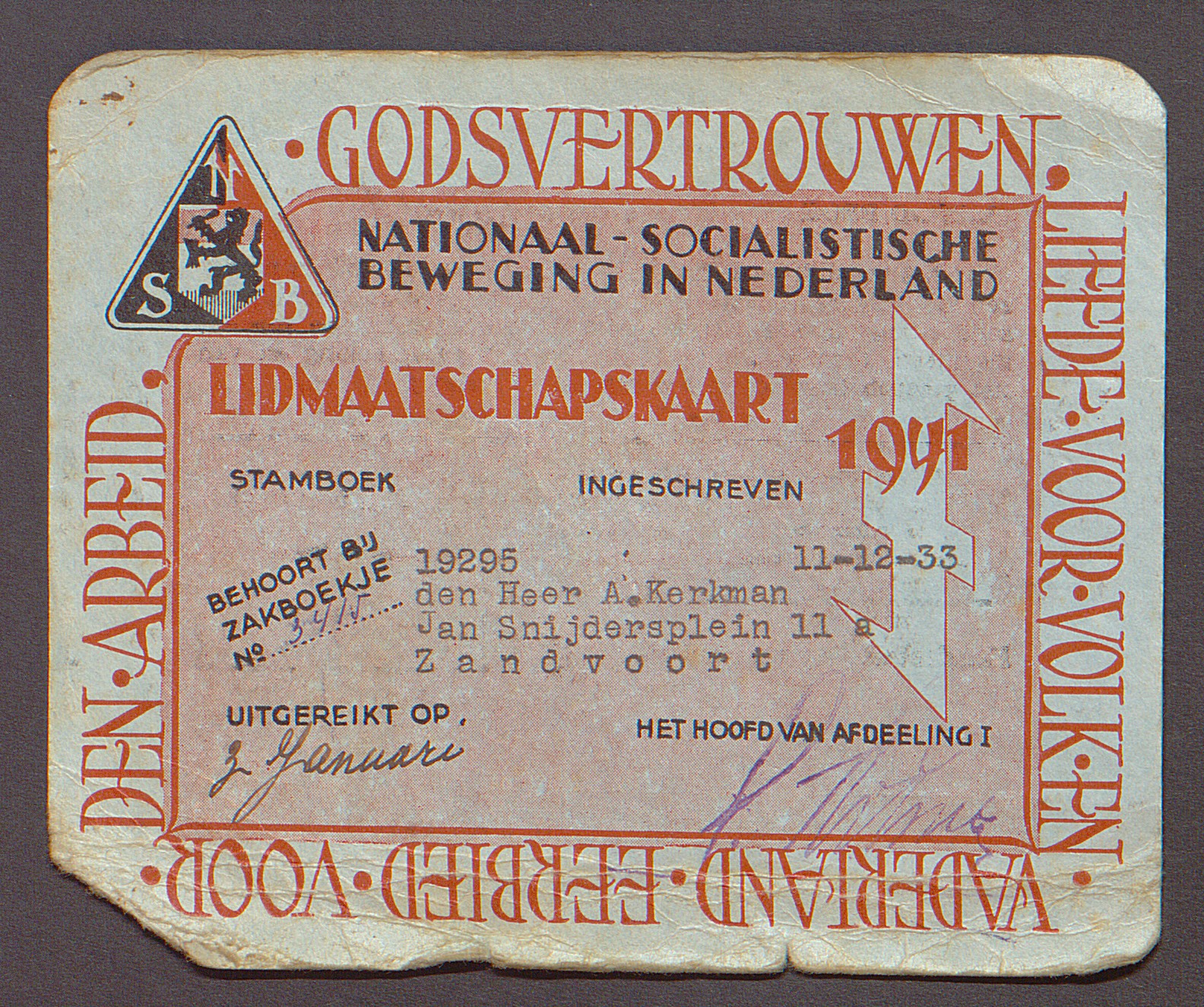

Documents include files on accused collaborators, notes from investigators, biographical information and witness statements. If someone was investigated for belonging to the Nazi affiliated NSB, their membership card might also be included.

Both the names of people who were convicted – some 20% – and those who turned out to be falsely accused are in the archive. Some 1,900 of those who were found guilty spent 10 or more years in prison.

Bruins said he understood the pain of people waiting for clarity because of the delay. In the meantime, he said, regional centres will be set up where people can go an access the files, removing the need to travel to The Hague.

“The archive is going to be opened,” he told Buitenhof. “It will be painful, but that is a pain we have to go through.” The war, he said, “still lives in our heads and hearts, 80 years on.”

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation