Secret mirrors, hidden scrolls: show of Asian Bronze old and new

Senay Boztas

They were created secretly in 17th century Japan, at a time when Christianity was forbidden by the shogunate: intricate, bronze ‘light-penetrating’ mirrors contained images of the crucifix and the Virgin Mary, to help devotees pray.

These magic mirrors are just some of the items on display in the Rijksmuseum’s autumn exhibition Asian Bronze, which opens on Friday.

The exhibition ranges from some of the first images cast by man, when the technique of creating bronze from an alloy of copper and tin was discovered in Asia, to a modern mirror made by a Kyoto craftsman who carries on the secret mirror tradition.

Taco Dibbits, director of the Rijksmuseum, said the germ of the show was an investigation into part of its own collection – a large Indian sculpture of the Hindu god Shiva. “Ten years ago we discovered it was cast from solid bronze, and bronze is a very difficult material to cast,” he said at a press view.

“In Europe at that time, in the 15th century, we weren’t able to cast solid bronze, it was always hollow, and it shows the incredible level of prowess in Asia at that time. Often in Europe, we look at Asian bronzes from an ethnographical perspective, but they are artworks…with an art history that shows an incredible beauty.”

Travel

The exhibition, with around 75 objects loaned from international collections as well as the Rijksmuseum’s own works, spans 4,000 years, religions from ancestor worship to Hinduism and Buddhism, and the mysterious properties of the metal itself. It represents countries including India, China, Indonesia, Japan, Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan, Nepal and Korea, and the living tradition of bronze in Asia, where there was a rich mine of tin, allowing them to develop the material.

Sara Creange, conservator of metals at the Rijksmuseum, said that the discovery of bronze allowed cultures to create objects that would both endure but also change with every new fingerprint. “When you add tin to copper, you get bronze,” she said. “The story of bronze began with copper, and copper was everywhere. Once humanity discovered, you can add tin to copper, melting these rocks together, you could change the properties of metal: it flows better, you can change the colour, you can change the hardness.

“So that’s really the first alloy that was man-made and traveled throughout the region. It also travelled west to Rome and Greece, the ancient world there, but the traditions in Asia really developed independently.”

One characteristic of bronze is the fact that it develops a greenish patina – reflected in the exhibition through the different wall colours, marbles and blocks on which the objects are displayed. Describing the beginnings of bronze, it features a standing female statue from Pakistan, around 2500BC, while religious objects include a Buddha seated under the hood of a seven-headed nāga, leaving Thailand for the first time since it was cast in the 12th or 13th century.

“Amazing”

Using a special form of scanning, neutron tomography, the Rijksmuseum has also examined the bronzes and found that secret scrolls and religious objects were even enclosed within some of the statues. The show includes ancient Japanese dōkatu bells that respond to your song, a stunning arch for visitors to walk through and objects spanning belief systems from ancestor worship to Buddhism that have long outlasted their makers.

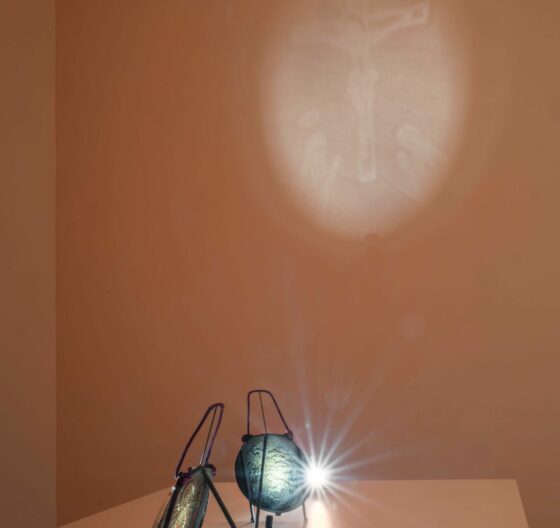

A display in the final room – including a commission of a modern mirror from a Kyoto craftsman – reveals the way bronze was used for secret worship in mirrors that project a hidden image only when light hits them at precisely the right angle. “When Christianity first was introduced, the believer had to worship it secretly,” said Ching-Ling Wang, curator of East Asian Art. “It’s a way of hiding the icons inside, which is rather amazing.”

One of the most interesting things about bronze, added Creange, is its materiality: it is a substance that endures for millennia and yet is always changing – whether or not it is polished. “It has what you call patina, a stable kind of corrosion,” she said. “The copper wants to return to its natural state. It comes from an ore and wants to go back to ore. Bronze has stayed as a tradition because its properties lend itself to use. It has the history of whoever has touched it: it really is alive.”

Sorrow

There is still a sense of awe surrounding these objects, created by people from all cultures and times to hold meaning, said Menno Fitski, head of Asian art at the Rijksmuseum. “Bronze can do everything,” he said. “It can sound like a bell, it can shimmer like satin, it can be cast in every conceivable shape and develops the most delicious patina that can even reflect light as a mirror.

“But it is amazing that people have been standing in front of these statues for centuries and centuries with their sorrows, with their private emotions, their worries, and this somehow forms extra layers around these sculptures…Their heartfelt sorrows stick to these objects, all of these layers of being. They end up being more than just pieces of metal.”

Asian Bronze runs from September 27, 2024 to January 12, 2025 at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation