O’o: new exhibition about nature in trouble opens in Amsterdam

Senay Boztas

The song of the Hawaiian Kauai O’o calling for a mate is a plaintive, minor melody.

It was a song this bird sang in vain. He came from an exotic species prized by Europeans for their bright, yellow feathers, their eggs taken by the cats and vermin that came with their ships. The O’o species finally became extinct at the end of the last century, and this 1987 recording of the last known male bird – singing with no female to hear him – is part of a new exhibition in Amsterdam.

“There were four sorts of O’os in the Hawaiian islands,” said curator Hans Mulder. “They were hunted by other animals like rats that came with humans… with dramatic consequences.”

The Allard Pierson, part of the University of Amsterdam, has a new exhibition about the kind of dramatic consequences that have come about thanks to the way Western Europeans have understood and interacted with nature through time.

With the help of items from some of Charles Darwin’s last letters to modern artwork from Damien Hirst, the show aims to give food for thought and be “not activist, but activating”, he said.

One of the most compelling media it uses is sound: the wistful calls of the bird welcome visitors to the exhibition. Another display shows the impact of the city on Dutch great tits, which raised the pitch of their song to rise above human traffic in Leiden, potentially making it harder for country birds to recognise them as the same species.

It is all part of a larger message about how modern humanity might choose to behave. “We don’t have to “save nature”, but we need to understand that if we ourselves want to survive, we need to do our best to preserve our ecosystem, which is in fact the whole earth,” said Mulder.

Chain of being

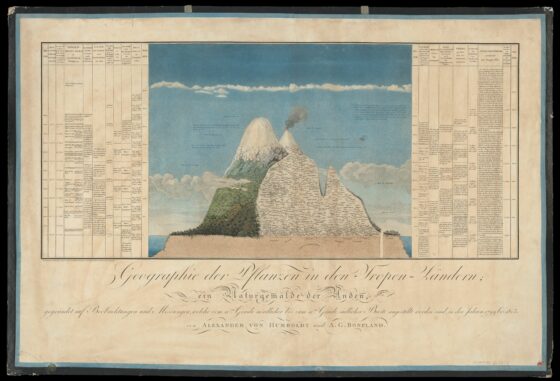

Various rooms look at different aspects of how Western Europeans understood nature, from early ideas about a “scala naturae” or great chain of being with humans above animals to the mania for collecting exotic objects during the colonial era.

The show includes drawings by German biologist Maria Sibylla Merian, who in 1705 published a book about insects in Suriname – a new copy of which has just been acquired by the Rijksmuseum.

Naming natural finds became another obsession in the 18th century, with a system introduced by Swedish biologist Carolus Linnaeus. He visited the Netherlands and is displayed in a preening portrait – perhaps representing, in his own view, a prime example of one of his designations, “homo sapiens”.

The exhibition tracks changes to the natural world, with habitats moving further up mountains due to modern climate change, the disappearance of species and the effects on entire food chains. It ends, however, with a message of “hope” and invitation for visitors to share their responses.

Haunting

“I don’t know if you should look at this with a feeling of guilt, but there are clearly things that happened that happened that we would not do now – and the perspectives of indigenous people and residents of an area were sometimes very different in how they lived with nature,” said Mulder. “We want to set people thinking.”

Els van der Plas, director of the Allard Pierson, said the exhibition and that haunting call of the extinct O’o help make their historic archive both relevant and compelling. “It is,” she said simply, “a very beautiful sound.”

The Call of the O’o: Nature under pressure runs from August 30 until January 26, 2025

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation