“Most of us want to cry these days, that cry can become poetry”

Gordon Darroch

Emigration is a theme of Maxim Ospiov’s stories and essays, which chronicle the decay of Russian society. And the Russian exile has now made Amsterdam his home.

The first time Maxim Osipov left his native Moscow, he was full of hope. It was 1989 and the 25-year-old doctor took advantage of the thaw in Cold War relations to board a Pan Am plane – the airline had resumed flights to Moscow the year before – and visit a school friend in San Francisco.

Two years later, with the Soviet Union on the brink of collapse, he returned to the United States to take up a research fellowship at the University of California in San Francisco to work at the laboratory specialising in echocardiography, a form of ultrasound used to examine the heart.

Even then, as the Soviet state unravelled, there was no question in his mind of leaving permanently. For one thing, his father had just died, leaving him as the head of a large family. But Osipov also wanted to contribute to his country’s revival, bringing Russian medicine out of the cold as a practitioner, as well as a translator and publisher of medical textbooks.

“I was very patriotic at that time, I would say,” says Osipov. “I wanted to build a new Russia. I was very happy that the USSR collapsed. I’m still happy about it. But I didn’t know what course life would take.”

The contrast with his last flight out of Moscow could hardly be greater. Eight days into the invasion of Ukraine, as rumours swirled that Vladimir Putin was about to close the borders and impose a state of emergency, Osipov gathered his family together and boarded a flight to the Armenian capital Yerevan. “It wasn’t clear what we were going to do,” he says. “I even had a plan to go to Georgia and practise medicine there.”

Gradually, a plan took shape. Osipov sent emails to friends and acquaintances all over Europe appealing for work and accommodation. He spent three months at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin, followed by a month in Switzerland. In Berlin he received a visit from Otto Boele, associate professor of Russian Literature at Leiden University and a man he now describes as a “good friend”.

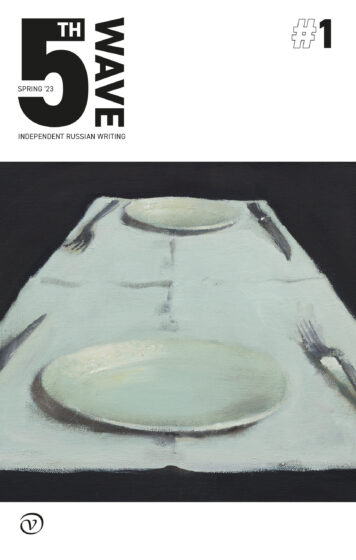

Boele offered him a one-year residency in Leiden, which has since been extended to four years. He now lives in Amsterdam and commutes to Leiden, where he teaches and publishes The Fifth Wave, a magazine dedicated to modern Russian literature. When we speak, he is preparing to give a talk on The Fifth Wave at the Crossing Border literary festival in The Hague.

Editing other people’s work has made him more aware of the challenges literature faces in wartime. “It’s very difficult to find good prose,” Osipov says. “With poetry it’s much, much easier. There’s a big choice of excellent poets. And I understand why that is. Most of us want to cry these days, and you can turn that cry into a lyrical piece of verse, but for prose you need something else. Prose about war is always written after the war.”

He rejects the idea that literature can change the world. The pen may be mightier than the sword, but this is the age of the long-range hypersonic missile. “When I am asked about the role of us writers, I say, we should look for humility. We should realise that the strength of the Ukrainian nation, of its army, of [president Volodymyr] Zelenskyy – those are the factors that will affect the outcome of this war. The main goal of the arts is to serve certain values, to serve beauty. That is what we are doing.”

Emigration is a theme of Osipov’s stories and essays, which chronicle the decay of Russian society in the early 21st century in unflinching detail. In Kilometre 101, a collection whose title refers to Tarusa, the small town 60 miles from Moscow where he lived and worked for 17 years, corruption and despair are woven into the fabric.

He describes how hospitals are forbidden to incinerate amputated limbs, but amputees have no wish to take their severed body parts home, so a homeless man ends up being buried with seven extra legs. His characters pursue careers and hobbies that offer a glimpse of a way out: medicine, languages, translation, chess.

But emigration does not bring redemption, merely the sense of exchanging one form of chaos for another. “Emigration is a disaster, a mental illness,” one character recalls his father saying. “And staying here, is that not an illness?” he retorts. “It is, just a different kind.”

Nostalgia and disorientation are always lurking: a woman travelling to Italy feels a sudden pang when she sees a headstone in Cyrillic script; a man finds himself on the wrong floor of a Russian apartment building because his mind has adopted the American numbering system. Being a physician, Osipov has inevitably been compared to Chekov, but his detached observation of people caught in hopeless moral tangles is also reminiscent of Turgenev.

Being an emigrant

So how does being an emigrant compare with the experiences of his characters? “I feel better than I expected,” Osipov says. “First, because I have things to do here. I know some wealthy people who found themselves abroad with nothing to do. So they go fishing and watch soap operas.”

Before the invasion of Ukraine Osipov lived in what he calls “internal immigration” in Tarusa. He practised medicine and writing in a provincial town without being active in cultural or political life. One of the differences between the Soviet Union and modern Russia, he says, is that the leaders of the former believed they were building a great power that would dominate global culture, whereas Putin’s Russia is claustrophobic and parochial.

In one of Osipov’s essays a patient is banned from listening to classical music in hospital because it is deemed bad for his health. “Life in the Soviet Union was dull and poor, with closed borders and very little hope,” he says. “It’s the difference between socialism and fascism.

“There was this image of the USSR that we were great and everyone was afraid of us. We sent rockets to the moon, we had the best hockey players. They cared about literature, they cared about movies, they wanted to display their talents. But Putin doesn’t care about music or literature or anything.”

Warped image

Nostalgia for the Soviet era is misplaced, he adds. “People in Russia today have a very warped image of the USSR. I tell young people: if you want an idea of how it was, go to the supermarket. Before you buy anything, wait for 40 minutes. Just stand there. Then go to the dentist and ask to have your dental work done without anaesthetic. And so on.”

The invasion in February 2022 came as a shock, but not a surprise. Osipov didn’t lose friends over it; that had happened already after the annexation of Crimea in 2014. “There were certain people to whom I had to say: look, you are a nice person, but we can’t talk any more,” he says.

His hopes of building a new Russia were extinguished even earlier, in 2008, when Putin installed his prime minister, Dmitry Medvedev, as president for four years, allowing him to bypass the constitutional limit on terms of office and return in 2012. “It was like a castling move in chess, where the king swaps places with the rook,” Osipov says with a resigned smile. “From that moment I clearly felt there was no future.”

No return

He is an exile now, he says, with no expectations of returning as long as Putin is president. “If I were 40, let’s say, I would see it as a break. But I’m 60 now. I had a life in Russia. This is more like a second life post mortem. So I feel grateful. Of course there are things I miss: my house in Tarusa, my parents’ graves, my doctoral work. But there are also gains, not just losses.”

One of the gains is that he lives in what he terms a healthy society now. He has said elsewhere that sick societies, like Russia, have a corrosive effect: he only became aware of his own prejudices against certain minorities after he left.

“[The Netherlands] is definitely much healthier than Russian society, and it is much healthier than American society, which I don’t know as well as Russia but I visited the United States many, many times,” he says. “In general it’s a healthy society. Although these days I’m annoyed and upset about the level of support Hamas gets in the West. The level of anti-Semitism in the world is much greater than I expected.”

One of the symptoms of Russia’s sickness is a deep sense of fatalism. “Putin met some soldiers’ mothers around six months ago,” Osipov recounts. “It was staged, of course. And one of them was crying because her son had been killed in Ukraine.

“He said to her: it’s understandable, but if he hadn’t, he’d have died from vodka or in a car accident. It wasn’t a slip, because they showed it on Russian television. And society accepts this. Nobody said he might become a great artist or a great carpenter or president of the Russian Federation. No, no: he’d have died of alcohol poisoning.”

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation