What’s all the fuss about immigration in the Netherlands?

The Dutch cabinet collapsed because of disagreements about potential measures to reduce immigration. So who is moving to the Netherlands, and why are they coming? An explainer:

The stumbling block which led to the cabinet’s demise was, officially, failure to agree on measures to reduce the number of refugee family members following a relative to the Netherlands. But the debate degenerated into mishmash of terminology and seemingly random figures. So what is the real picture?

Some 224,000 people moved to the Netherlands last year, CDA leader Wopke Hoekstra said after the cabinet collapse. There were 400,000 migrants in 2023, VVD stalwart Henk Kamp told Nieuwsuur. Justice minister Dilan Yesilgoz claimed family members are moving to be with family members ad infinitum and the ChristenUnie, who appear to have pulled the plug on the cabinet, said the whole dispute boiled down to just 5,000 people joining their relatives every year.

How many people moved to the Netherlands in 2022?

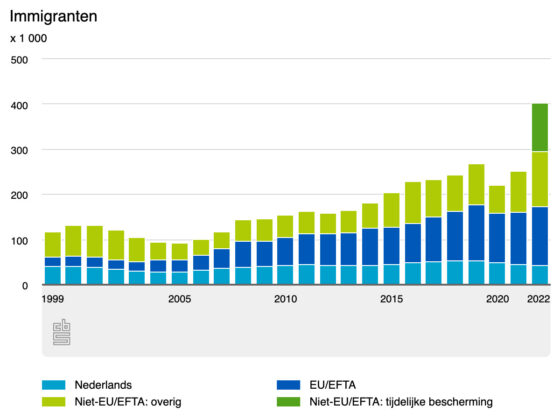

In total, 403,000 people moved to the Netherlands in 2022 and 174,000 people left, according to updated figures published by national statistics agency CBS last week. Some 80% of those leaving had roots abroad.

That means the number of new arrivals was a net 229,000 last year.

Of the total people who came to the Netherlands in 2022, almost 44,000 (11%) were Dutch nationals returning home after a spell working or studying abroad.

Almost 129,000 of them (32%) came from the EU and European Free Trade Association (Efta) countries and 108,000 (27%) came from Ukraine.

A further 122,000 people (30%) came from outside the European Union and Efta, including 26,000 who came to work under various highly skilled migrant schemes. They also brought with them 39,000 family members – mainly partners and school-age children.

Some 46,000 were refugees, including family members joining them in the Netherlands. Most of those came from Syria.

Is the total more than in recent years?

Yes, but not by much if you ignore the two coronavirus years. The 150,000 increase in new arrivals in 2022 is largely due to the influx of Ukrainians fleeing the war and the catch-up impact of coronavirus which severely restricted travel. The number of non-EU nationals who came to work, for example, was up 35%.

So Europeans account for the biggest group of new arrivals?

Yes, and that has been the case since 2007, apart from in 2016 when there was a surge in refugees from Syria and Iraq. Under EU freedom of movement rules, nothing can be done to reduce the number of EU nationals coming here.

What about refugees and their families

The UN’s refugee programme puts the number of new asylum seekers arriving in the Netherlands last year at 35,000, plus 11,000 family members.

According to the CBS, 27,600 “asylum migrants” were registered in the Netherlands last year and 11,000 came to join close family members who had been given official refugee status. That figure is up slightly on 2021, when coronavirus was making foreign travel difficult.

Around half came from Syria, followed by Turkey, Afghanistan, Yemen and Eritrea.

The UNHCR figure includes everyone who makes a new asylum request. The CBS figure only includes asylum seekers who are officially registered with their local authority.

And this year?

The government said in April it expects 70,000 refugees and family members to come to the Netherlands in 2023, but so far the figure is set to be well below that. Just over 18,300 new asylum seekers reported for processing between January and the end of May, which is down 1,300 on last year.

If the pattern were repeated throughout the year as a whole, the total number of new arrivals would be less than 45,000.

What’s the score with family members?

In total, refugee family members – the group which the government was trying to restrict when it collapsed – accounted for just 2.7% of the total immigration stream in 2022.

And according to refugee aid group Vluchtelingenwerk, which guides most family reunification processes, the claim made by Yesilgoz that family members are bringing in more and more relatives is “fiction”.

It says family reunification programmes are restricted to partner and children under the age of 25, and that grandparents, aunts and uncles are excluded unless there are extremely special circumstances. At most, Vluchtelingenwerk says, there were just a handful of cases last year.

In addition, it points out, a refugee’s family member would have to make their own application for refugee status to be able to bring in other relatives in the first place.

So what is all the fuss about?

Basically, the government’s failure to provide proper housing and other services for those that do arrive. That led last year to people sleeping outdoors or on chairs, to children being denied schooling and support.

In total, the COA refugee agency has nearly 54,000 people in its care, but almost 16,000 of them have formal refugee status and should be living in ordinary housing.

There is, after all, a housing crisis in the Netherlands, largely due to the fact that not enough homes have been built for years. The government says we need at least 900,000 new homes to meet demand by 2030 and the shortage is currently 390,000.

In addition, COA says just 3% of its beds were occupied at one point last year by people from safe third countries, such as Morocco, Tunisia and Georgia, despite the far-right’s claims that all refugees are “fortune hunters“.

What about non-EU nationals?

Last year, 26,000 people came to the Netherlands as a kennismigrant and nearly 3,000 came on one of several other schemes for highly-skilled non-EU workers, according to the CBS figures.

A kennismigrant, literally, a knowledge migrant, is someone who comes to the Netherlands on a special visa under the highly skilled migrant scheme, as a researcher or via the start-up visa scheme. These schemes entitle them to work in specific fields where there is a shortage of local expertise. EU or Efta nationals are not counted as highly skilled migrants.

Highly skilled migrants have to meet strict rules on salary, earning at least €36,000 if under the age of 30 and €50,000 if older.

The CBS says that at the end of 2021, 87,000 “labour migrants” from outside the EU and Efta were working in the Netherlands, and 46% of them were on highly skilled visa schemes. A further 11% were working as scientific researchers.

So what are all those Europeans doing?

In total, there are almost 900,000 EU nationals living in the Netherlands.

Many are working, but a large percentage are also family members, some of whom will have been born in the Netherlands but don’t (yet) qualify for Dutch nationality.

Some are branded as expats. Many of them are labeled as arbeidsmigranten – labour migrants – a term which has no legal definition but is generally used to describe people, often from central and Eastern Europe, who work in low-skilled jobs in horticulture, slaughterhouses, the food industry and logistics. They are often exploited by staffing agencies, employers and landlords and some experts have suggested the Netherlands rethinks its economic strategy to reduce its reliance on cheap labour.

What about students?

There are 122,000 international students currently studying at a Dutch university, three and a half times as many in the 2005 academic year. Around 15% of the student body is not Dutch.

According to CBS figures, 21,000 new students arrived last year and are registered with a local authority. By far the most foreign students – over 22,000 – come from Germany, followed by Italy, Romania, China and Spain.

The government is planning to reduce the number of English courses and make learning Dutch a requirement for most following mounting pressure from MPs and educational institutes to reduce the number of foreign students.

So how does all fit together in the general population ?

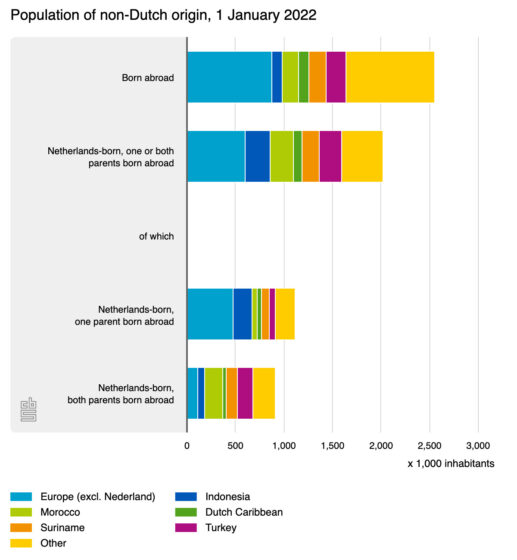

In total, some 15% of the population of the Netherlands (17.6 million at the beginning of 2022) were born abroad and an additional 12% had at least one parent who was born in another country.

In short?

The government collapsed over a small number of people who cannot, under international treaties signed by the Netherlands, be kept out anyway.

And as for the 5,000 family members ChristenUnie leader Mirjam Bikker referred to during the parliamentary debate? She too was being a little relaxed with the figures.

In fact, the VVD’s plan was to restrict the number of family members coming to the Netherlands to live with relatives from war zones to 2,200. War zone refugees are so-called B category refugees as opposed to refugees fleeing persecution (A). If the VVD had succeeded, that would have meant 5,700 children and partners would not have been allowed in last year, 700 more than Bikker herself stated.

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation