Elections: Why climate change is raising the stakes for water authorities

The old saying goes that God created the earth, but the Dutch built the Netherlands. In a country where one-third of the land is below sea level, keeping the ground dry is a process of careful, constant management.

When voters in the Netherlands choose the board of their local water authority on March 15, they are influencing not just the political direction of the country but its physical shape, potentially for generations to come.

The 21 Dutch regional water authorities are a largely invisible tier of government, but a vital one. Legally they have three core tasks: to maintain the dykes, to purify the water that goes out to households and the canals, and to regulate water levels in order to protect the land from the twin threats of drought and inundation.

But as climate change and the agricultural reform move up the agenda, the water authorities are becoming increasingly political. ‘When we talk about these elections people often reply: everyone wants clean water and secure dykes, what kind of political choices do they have to make? But the way we do that can vary greatly,’ says Jane Alblas, spokeswoman for the Association of Dutch Water Authorities (UvW).

‘For instance, you can decide you want to raise the dykes as high as possible as we’re used to doing, but you can also say that as the sea levels rise, there will come a time when we need to make room for water.’

‘On clean water, we have to conform to European standards, and you can say that that’s ambitious enough. But you can also say we need to invest in better water purification systems to deal with new challenges like microplastics and medicine residue, and that’s a considerable investment.

‘Or you can say: we think we need to do more at source to stop that pollution getting into the water in the first place, so we should put more effort into stricter rules and enforcement for polluters.’

- Use the Citisens vote compass (stemwijzer – page in Dutch) to help you choose between the candidates

Right to vote

Unlike the provincial assemblies, which are only open to Dutch citizens, the water authorities are chosen by all residents in their area. Everyone who was registered with their municipality on January 30 and has a valid residency card should have received a blue polling card, or stempas, by post. Around 900,000 foreign nationals are eligible to vote this year, according to the government statistics agency CBS.

Water authorities are the oldest branch of government in the Netherlands. The first, the Hoogheemraadschap van Rijnland, was established in Leiden by Count Willem II of Holland in 1255. The elected board makes policy decisions at its public meetings and appoints a board of officials to oversee the day-to-day running of the water network, headed by a ‘water mayor’ or dijkgraaf.

Their boundaries straddle municipalities and provinces, but they have persisted as autonomous elected bodies mainly because they are funded by a direct tax, the waterschapsbelasting.

‘We have a fairly unique financial set-up,’ says Alblas. ‘It’s important in a country on a Delta like the Netherlands that water management doesn’t have to compete for funding with things like youth care.

‘But the fact that you pay a tax means you should have a say in what happens to that money. And when you look at all the social issues around water and public space, these are all matters that affect people directly, so it’s important that their voice can be heard.’

More candidates

The growing significance of the regional water authorities can be gauged from the fact that the number of candidates for this year’s elections is 30% higher than in 2019, with 4,667 candidates representing a total of 255 parties.

Turnout is also on the rise, helped by the decision to combine the water board elections with the provincial assemblies. Last time out 51.3% of the electorate voted for a water board candidate, up from 43.5% in 2015. In 2008, the last time the boards were chosen in a standalone election, just 22.7% of voters bothered to turn out.

‘Because the provincial assemblies choose the Senate it’s seen as a sort of mid-term election for the cabinet, and obviously we benefit from that,’ says Alblas. ‘If people are in the voting booth they can just as well fill in both ballot papers at the same time.’

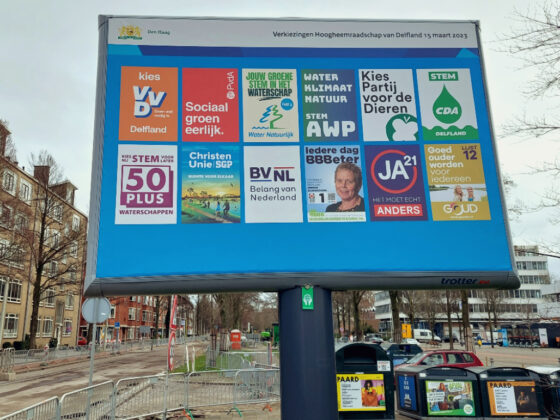

Most of the national political parties have water divisions, though only the right-wing liberal VVD and the farmers’ party BBB are standing in every region. GroenLinks, D66 and Volt have thrown their weight behind Water Natuurlijk, a party that campaigns for more sustainable water management and has the largest number of seats across the 21 water boards.

Climate change

‘I think it’s becoming more political and that’s partly to do with climate change,’ says Anieke Kranenburg, who is heading the list of candidates for Water Natuurlijk in Vechtstromen, a region that covers parts of Overijssel and south-east Drenthe.

‘There are parties like the VVD who say we should concentrate on the core tasks as prescribed by law and not spend money on extras. And there are parties like ours who argue the water board should play a role in generating energy from waste water and pay more attention to nature and biodiversity.

Even in a country the size of the Netherlands, the challenges vary considerably between regions. While Limburg was inundated by river flooding two years ago and the west coast is vexed by the prospect of rising sea levels, eastern parts of the country, such as Vechtstromen, are experiencing more frequent droughts as summer temperatures rise.

‘It’s increasingly affecting the world people live in and coming ever closer,’ says Kranenburg. Compared to four years ago you can see people starting to think it maybe important after all.’

‘It’s our future’

At the age of 29, Kranenburg stands out among her colleagues, who are overwhelmingly white, male and semi or fully retired. She combines her duties at the water authority, which takes up around 12 hours a week, with a full-time job as a postgraduate researcher and tutor at Tilburg University.

Her involvement started when she received her water authority tax bill as a student and wanted to know where the money was going. ‘I was just curious, so I went along to a meeting. Everyone looked at me in surprise because nobody ever came to watch. They thought I was a trainee in communications.’

Kranenburg felt the water authorities’ boards should be younger and more diverse, and decided to become more actively involved. ‘You don’t change the course of a river just like that: these are major interventions involving large sums of money,’ she says. ‘So it makes sense for young people to have more of a say, because this is about our future.’

She has worked to make Vechtstromen more accessible and transparent, setting up livestream feeds of the meetings and promoting her work in Instagram posts. ‘Water and nature make for nice pictures and it’s nice because young people aren’t into writing e-mails so much, but you can send a DM quickly, so that keeps me in touch with them.’

Voters have even more influence this year as a result of a reform pushed through by D66 and GroenLinks that reduced the number of reserved seats allocated to interested parties. Until now nature organisations, farmers and the business community were each given two seats on each board (out of between 18 and 30, depending on the population of the water board area) to reflect the direct impact of its decisions on their activities.

More elected seats

The two political parties wanted to abolish the seats for agriculture and business. After a late compromise the seats for farming representatives were retained, but the outcome still means two more seats will be chosen by voters this year.

Alblas questions whether the abolition of the reserved seats will make a significant difference to the composition of the boards. The business community has responded by setting up a political party, Bedrijfsbelangen, to try to retain the seats via the ballot box.

‘I’m not sure it’ll make a big difference because in the end they’ll find their way back to the boards through political parties,’ Alblas says. ‘Just as there are a lot of farmers on the boards because they’re more aware than the average person of what they do and parties like BBB and CDA have a support base in the farming community. But we’ll see what happens.’

Kranenburg argues that cutting the number of reserved seats will make the water authorities more accountable and relevant to voters. ‘Your vote and my vote will count for more, and that means it’s very important that people get out and vote, because residents will have more influence in these elections.’

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation