Fake news, cannibalism and a human tongue: the disaster year of 1672

An exhibition at The Hague’s Historisch Museum focuses on one of the most turbulent events in Dutch history and includes propaganda and a preserved human tongue among its highlights.

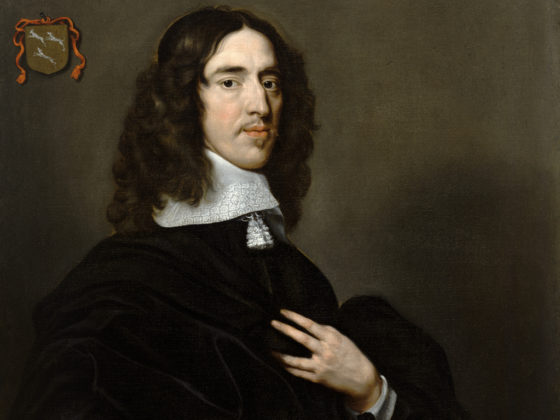

The ‘disaster year’ of 1672 is best known for the rapid and brutal downfall of the De Witt brothers, who had governed the United Provinces of the Netherlands for the best part of two decades.

At the start of the year Johan de Witt was the most powerful man in the Republic. As Grand Pensionary of the state of Holland he had ended one war with England, triumphed in another and turned the Netherlands into the most formidable naval power in Europe.

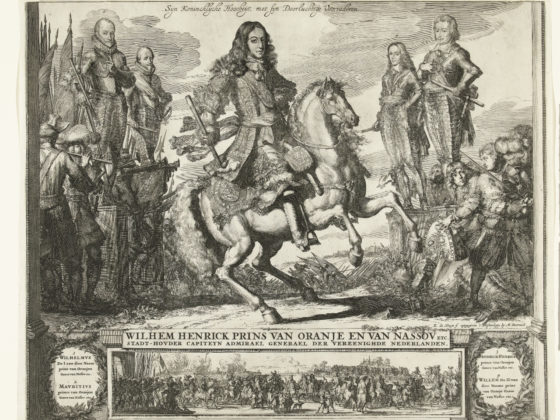

In March war again broke out with England, but this time the Dutch also faced invasion from France and two German bishoprics. The people grew restless and clamoured for De Witt’s rival, William of Orange, to be installed as kapitein-generaal, or head of the army.

The net closed tightly on De Witt and his brother Cornelis, who was accused of plotting to kill William and taken to the Gevangenpoort prison in The Hague. When he refused to confess under torture, Johan was invited to fetch him from jail and take him into exile.

But soon after he arrived a mob gathered outside the prison gates, dragged the brothers outside, lynched them from the public gallows and cut pieces from their corpses, either as souvenirs or as grisly snacks. None of the looters or the cannibals was ever caught.

Exactly 350 years on from the rampjaar, an exhibition at The Hague’s Historic Museum focuses on its turbulent events and how public opinion turned so dramatically against the De Witts, with deadly consequences.

Propaganda war

‘We have a lot of objects relating to the events of that year, like a preserved tongue and finger of the De Witt brothers, so it seemed like a good time to put them on display,’ says museum spokesman Martijn van Ooststroom.

‘But we didn’t just want to give a history lesson. We wanted it to appeal to a broader audience and link it to contemporary events like the coronavirus pandemic in 2020.’

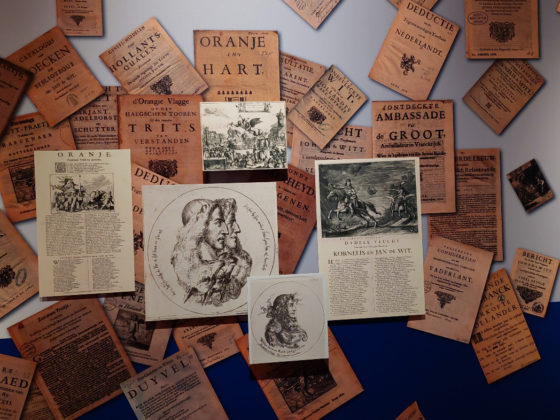

The exhibition shows how propaganda sheets, a relatively recent invention – the first newspapers had appeared in Amsterdam in 1618 – played a key role in radicalising public opinion as the situation in the country deteriorated.

Thousands of pamphlets were published during the year and distributed by hand, depicting the De Witt brothers as self-serving elitists who were out of touch or, worse, secretly in league with the United Provinces’ enemies.

‘Literacy was quite high in the Netherlands in the 17th century, so pamphlets had a real influence,’ says Van Ooststroom. ‘They’d been around for decades but this was a real explosion.

‘You can compare it to social media: these pamphlets were handed out in inns and other places, so a lot of people were able to read them.

‘They contained a lot of lies and false information: that Johan had sold the Netherlands to the king of France, or that he was secretly a papist, which was one of the worst things you could be in the Netherlands in the 17th century, or that the two brothers were devils.

‘At some point it started to stick, which is something we’ve seen recently as well.’

Orangists v regents

The Netherlands in 1672 was polarised between the regents and merchants who supported De Witt, and the Orangist supporters of Prince William.

Ultimately it was William who prevailed. He was elected as Stadholder, the dynastic position previously held by his father, in July, after harnessing the pamphleteers’ support. Shortly afterwards De Witt resigned from office as he recovered from a violent attack in the street.

Suspicions are rife that William had a hand in the murderous campaign against the De Witt brothers in August. The mob outside the prison in The Hague emerged quickly while Johan was inside visiting his brother, after Cornelis’s newly released cellmate started spreading false rumours that he had been found guilty of treason.

The fact that free beer was distributed among the crowd strengthens the view that the protest was not entirely spontaneous, but no evidence has been found that William was directly involved.

William’s rise

In 1654 De Witt had secretly signed an order as part of the peace treaty with England, then a republic ruled by Oliver Cromwell, that banned any member of the House of Orange from holding the office of Stadholder again. But after the restoration of the English monarchy, the Dutch authorities ruled that the Act of Seclusion, as it was known, was no longer valid.

William thus had a vested interest in overthrowing De Witt’s government, and saw his chance when England and France joined forces to invade the Dutch republic, under a secret treaty agreed in 1670.

‘He was very much an opportunist,’ says Van Ooststroom. ‘People were tired of De Witt, who had been in power for almost 20 years and was seen as out of touch with the common people.

‘He ignored the growing resentment for too long and didn’t respond until it was too late. By then public information and his regents had turned against him. He issued his own pamphlets, but they were very legalistic and didn’t come across well.’

‘At the same time the Netherlands was overrun because it didn’t put up a proper defence. He dismissed the idea that the two kings would work together against the Dutch republic and that meant he didn’t have time to reorganise his army.’

Pandemic parallels

The parallels with the present day are explored in a second room, which compares the unravelling crisis of 1672 with the coronavirus pandemic of 2020. Early attempts to prevent the crisis inspired a mood of solidarity, but as events unravelled it gave rise to divisions, plummeting trust in leaders and a search for scapegoats – not unlike the reactions to the lockdowns of the last two years.

An innovative sideline is a series of Twitter accounts set up in the name of Johan de Witt and others in his circle to promote the exhibition. The tweets are based on extracts from De Witt’s letters and diaries, complete with snarky replies from fictional pamphleteers.

‘We started the Twitter accounts before the exhibition to draw attention to it, but also so we could use the information from his letters to his friends, his family, officials and diplomats,’ says Van Ooststroom.

‘We have a huge amount of his correspondence: he wrote several letters a day. We know what his feelings were, which enables us to follow the development of the rampjaar day to day through his eyes.’

The Disaster Year exhibition is on show at The Hague Historic Museum until November 13

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation