Mondrian biography paints new picture of misrepresented artist

For six years, the most comprehensive biography ever written on the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian was only available in Dutch. Thanks to a new translation, English-speaking audiences can now learn more about one of modernism’s most important figures.

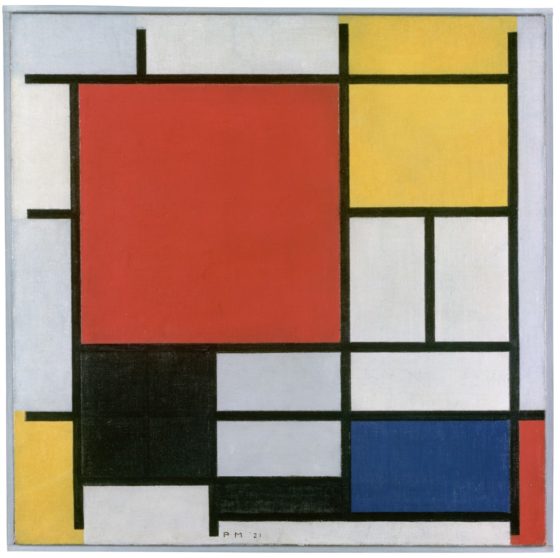

Mondrian, it turns out, was not the man we thought he was. A century on, the influence of his iconic grid paintings is still everywhere to be seen, from architecture and interior design, to clothing on the catwalk. Yet, according to a more nuanced portrait of Mondrian proposed by Hans Janssen’s meticulously researched Piet Mondriaan – Een nieuwe kunst voor een ongekend leven (2016), translated into English this year on the 150th anniversary of Mondrian’s birth, much of the received knowledge on the man behind the easel misses the mark.

Released in the UK in June, with a US edition due on 27 September, the 424-page translation Piet Mondrian: A Life is the first comprehensive biography on Mondrian ever published in English.

The work is the result of years of study by Hans Janssen (1954-2021), former chief curator of the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, home to the world’s largest Mondrian collection. His painstaking examination of source material − including previously unknown letters and manuscripts − permits a closer reading of Mondrian’s oeuvre than ever before and promises in the introduction, ‘a fuller picture of the man, and a more pleasurable experience of his work’.

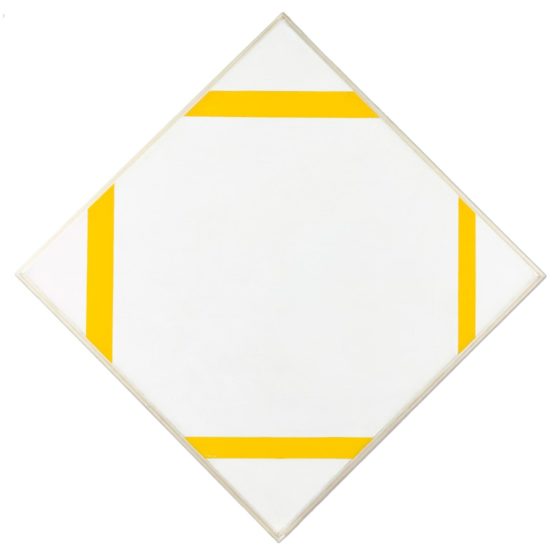

Above all, the biography puts paid to the myth that Mondrian, the most dogmatic of the founders of the De Stijl movement (abstract, ‘neoplastic’ art restricted to straight lines and primary colours), lived life as a hermit, absorbed in his work. On the contrary, he was a huge jazz enthusiast, a fantastic dancer and had a great sense of humour.

In Paris (1912-1914 and 1919-1938), in particular, he immersed himself in the city’s bohemian nightclub scene. He kept society with poets, playwrights and painters: Cocteau, Stein, Picasso, Man Ray; and the singer, dancer and actor Josephine Baker, whose ‘visible, tangible energy’ (Janssen) he was very taken with, seeing a kinship between her appealing exterior and private interior and his own artistic endeavour to pierce the universal laws underpinning beauty.

‘In 1920 and 1921, the avalanche of new experiences and friendships unleashed in Mondrian an inexhaustible urge to work,’ writes Janssen. Mondrian, we learn, was far from isolated. In fact, the more he left his studio, the more prolific his painting. His love of concerts and dancing nourished his work and gave it an important musical element often overlooked by critics.

But not Jansen. ‘He gradually came to realise that a good painting … had its own inner rhythm that came from the interaction between the visual elements, of which position and proportion were the most important,’ he writes, and he quotes a 1922 newspaper interview where Mondrian hints at how jazz music’s ‘sounds that suddenly cease’ and dance’s ‘equilibrium through opposition’ influenced his grid compositions.

Mondrian even named a series of paintings after his beloved fox trot, communicating the same slow, slow, quick, quick rhythm as the eye dances around the canvas. And when the Netherlands threatened to ban the Charleston in 1926, he told De Telegraaf that he might never return there.

Despite a strict religious upbringing in Amersfoort, Mondrian was not the monk some historians have made him out to be. Though there’s evidence in the book that he ended relationships if they compromised his ability to paint, Mondrian enjoyed many romantic liaisons and − with his slicked back hair, tailored suits and nifty dance steps − he was hugely popular with women.

Nor did his intellectual circle and his devotion to his art make him haughty. Instead, Janssen paints the picture of a likeable man who was ‘kind-hearted and never mean-spirited’. ‘He may have had strong opinions, but he was not quick to judge,’ he writes.

Unusually, the biography features interludes where we are given access to Mondrian’s thoughts or witness imagined conversations. Though based on documentary evidence, these intimate moments drew mixed reviews from critics. But they are perhaps best understood as testament to the deep connection Janssen felt to Mondrian − sometimes even feeling he was becoming him − and his desire to bring his hero to life for readers.

Readers of the biography are also treated to vivid descriptions of Mondrian’s studios in the Netherlands, France and the US. We follow Mondrian as a student in the 1890s, going door to door in Amsterdam’s De Pijp district hawking his landscape paintings, and we hear how, in 1940, he was almost torpedoed at sea as he fled the UK to start a new life in New York.

Curator Caro Verbeek, who took over from Hans Janssen at the Kunstmuseum Den Haag in 2021, told DutchNews.nl that Piet Mondrian: A Life has brought ‘new knowledge and new insight about Mondrian as a human being and an artist’ and how the two are intertwined, and elicited ‘enthusiastic reactions from all over the world’.

Verbeek, who works at the desk where Janssen once sat, once found a button beneath it which belonged to him. Janssen suggested she return it to him in person, but died before a date was set. The button is now pinned to Verbeek’s computer as a reminder of his contribution to art history. It is one of her roles at the museum, she says, ‘to keep communicating Hans’s message that Mondrian was not anti-social, not cerebral, but that he was intuitive and highly social’.

With the Kunstmuseum’s recent exhibition Mondrian Moves, inspired by Janssen’s biography, and the tour ‘Clapping to the beat of Piet’, Verbeek has stayed true to Janssen’s legacy. ‘No-one knew Mondrian as well as he did,’ she says.

Buy this book from the American Book Center

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation