Wassenaar honours man who saved the graves of resistance fighters from oblivion

Wassenaar local council has named the cycle path that leads past the memorial on the World War II execution site Waalsdorpervlakte after Piet Kuijt, who prevented the graves of resistance fighters from disappearing forever.

Kuijt’s work only came to light recently through the efforts of Edward Verheij, who became intrigued by the story which was doing the rounds at dune water company Dunea where he is manager.

Katwijker Kuijt, who worked as a marram grass planter at the previous incarnation of the company had marked the graves of the resistance fighters, the story went, foiling the attempts by the Nazis to erase every trace.

‘Kuijt had been given permission to enter the Sperrgebiet but he was kept away when the Nazis carried out executions. He knew the area so well that he could tell by the way the dune sand had been moved where the graves were,’ Verheij said in NOS radio programme Met het oog op morgen. ‘It was incredibly dangerous and if the Germans had found out what he was doing they would have shot him as well.’

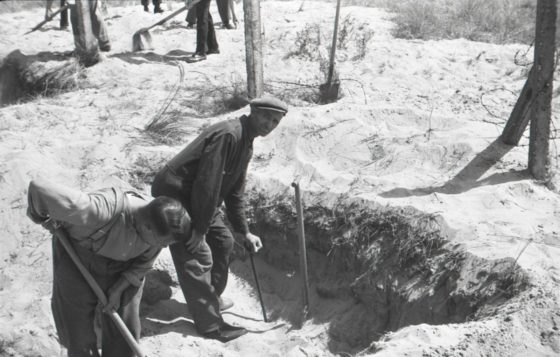

How exactly Kuijt marked the graves to which he could later lead a party of grave diggers is not known, his grandson Peter said. ‘He was very reserved, not easy to talk to. He never said anything about it. My father now sees him in a completely different light. What my grandfather saw affected him deeply and in those days you could not go and talk to someone. He had to deal with it alone.’

Photos of the site show that Kuijt, then 53, was among the diggers, most of whom were members of the pro Nazi party NSB.

Between 250 and 280 resistance fighters were executed on the Waalsdorpervlakte which is the scene of a remembrance ceremony every year on May 4. The last executions took place there on March 8, 1945 in retaliation of the attempt on the life of SS leader Hanns Rauter. Some 38 people were killed, among whom journalists of resistance newspaper Trouw.

Not all the bodies could be identified in the years after the war. DNA research identified another one of the victims as recent as 2010 but 27 remain nameless.

It is difficult to determine why Kuijt, who died in 1972, decided to take on the dangerous job of marking the graves, his grandson said. ‘I think he thought those people should be found so their families could say goodbye. I am very happy that he did this because otherwise they would never have known what happened to their loved ones.’

Kuijt refused the resistance medal after the war and his grandson is sure his grandfather would have been reluctant to accept this honour but perhaps secretly pleased as well. ‘I think he would be proud if only he didn’t have to blow his own trumpet about it. But the family is very proud of him.’

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation