Vincent in his own words: Van Gogh museum opens rare display of fragile letters

From a letter in which Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin describe brothel visits, to Vincent’s first note to his younger brother Theo, the Van Gogh Museum is displaying an extraordinary collection of the artist’s correspondence.

‘Your loving Vincent’, which launches on Friday and runs for three months, unites 40 of the Dutch artist’s 820 letters with some of his most famous paintings, including two on loan from private collectors. The extensive correspondence, which has allowed scholars to have such a close understanding of Van Gogh’s art and personal struggles, is very rarely shown because it is so sensitive to light.

Emilie Gordenker, director of the Van Gogh Museum, said that the artist’s letters feel particularly poignant during this pandemic. ‘This subject is very suitable for these times because we are all engaged in trying to communicate with each other in one way or another,’ she said.

‘Most of the letters are from Vincent to Theo, about art, about his own development, his emotional state and family. We very rarely display them as they are very fragile and mostly live in the dark.’

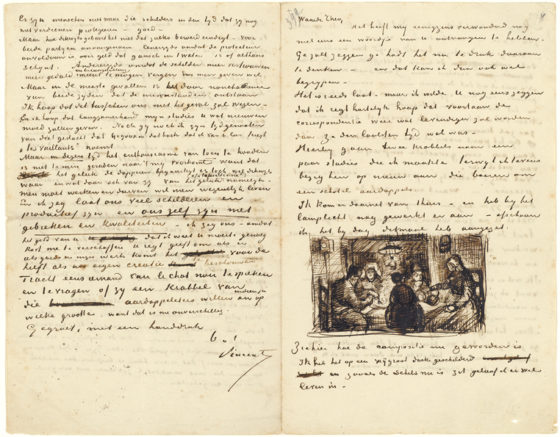

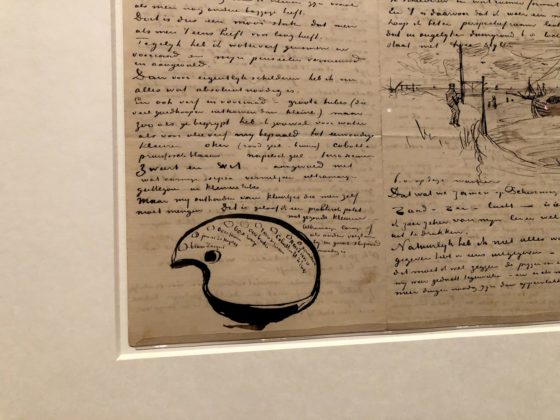

However, for the first time in a decade, the museum is displaying some of Van Gogh’s most interesting letters, including two recent acquisitions from private collections. The letters, many of which include simple pen and ink sketches, are displayed next to the paintings they refer to, including Bedroom in Arles and The Potato Eaters.

Nienke Bakker, senior curator, said that they give a unique insight into the artist’s development and ambitions, and hopes that the exhibition will introduce them to a new generation.

‘Vincent van Gogh wrote a lot of letters, and 820 of them survived, many of them thanks to his brother Theo. Together, they are the main characters of this exhibition, which is about the relationship between art and letters, thanks to the beautiful sketches he makes, and the close bond between brothers which intensified after Vincent decided to follow his brother’s advice to become an artist. Everything he’s working on, he writes down and he also writes beautifully.

‘But the letters are still relevant: they are about subjects that we can identify with and that draw us together like friendship, brotherly love, loneliness, need, love, ambition, fights: it’s all there. They still feel contemporary, accessible and we find ourselves in them. The letters are a hidden treasure in our collection.’

To mark the exhibition, a new anthology of Vincent van Gogh’s most interesting 76 letters have been published in English and in Dutch, an online anthology is available and a podcast series has been recorded with Dutch writers, actors and musicians reading from the letters.

The Van Gogh Museum display is presented in Dutch and English, although in fact a third of Van Gogh’s letters and all of his later ones are written in French after he moved to France. Many of them contain great detail about the paintbrushes he needs, the colours he has bought and techniques he was trying, says Bakker, because Van Gogh was funded by his art dealer brother and was ‘justifying where the money was going!’

The letters deal with his early interest in working figures such as fishermen at Scheveningen, a soup kitchen in The Hague, and one of his early girlfriends, a former prostitute. Later letters describe his ambitions to create an artists’ colony in the south of France, including a feisty 1888 letter written with Paul Gauguin to artist Emile Bernard describing their ‘excursions in the brothels’ and recently bought by the Vincent van Gogh Foundation for $210,600.

After he fought with Gauguin, mutilated his ear and suffered a breakdown, Van Gogh admitted himself to an asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence: one letter on show appeals to his brother Theo for paintbrushes, which he thinks might help him recover. The exhibition also displays Van Gogh’s final letter, written four days before he shot himself in the chest on 27th July 1890, and another unfinished version found by his brother on his body.

‘The last letters are incredibly sad,’ says Bakker. ‘He feels like a burden to Theo with no prospect of getting better. It is tragic that an artist who made such beautiful canvases ended it all.’

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation