‘They were proud of what they were doing’: A Dutch Holocaust survivor’s story

Henry Fenichel’s happy childhood in The Hague was destroyed by the Nazi occupation in 1940 and his subsequent deportation, as a Jew, to Bergen-Belsen. But his quick-thinking mother saw an opportunity for escape, and Fenichel – now 82 – survived to tell the story.

On April 15th it will be 75 years since Bergen-Belsen was liberated, two months too late for its most famous inmate, Anne Frank. Physics professor Henry Fenichel, who made the same gruesome journey from Westerbork to Bergen-Belsen, was more fortunate. Born in The Hague in 1938, but living in the USA since 1953, his survival has compelled him ‘to bear witness’. ‘I figure that’s my mission in life, along with an occasional lecture in physics,’ he jokes.

For a long time Henry was silent, focusing on family life and forging a career for himself, until ‘some of the nonsense that goes around the world politically’ impelled him to speak out. ‘Look at the terrible things that are happening! As human beings, we haven’t learnt the lesson,’ he says.

Nazi occupation

The last vestige of a normal childhood is a photograph of Henry, an only child, with his parents Moritz and Pessel – the only picture he has of all three of them together. ‘Soon after that, all hell broke loose and the Nazis invaded and life changed,’ he says.

However, a stealth approach meant that the country’s 140,000 Jews were not yet fully aware of the danger they were in. ‘When they invaded Holland, they didn’t immediately round up the Jews. They were very smart about what they did,’ says Henry. ‘But then all of a sudden, the cop on the street corner, instead of being a Dutch cop, would be a Nazi cop or a Dutch collaborator – and there were plenty of those.’

By 1941, almost all freedom of movement and information had been banned. Jewish businesses were shut down, students were expelled from universities and lists were drawn up of Jews to be sent to forced labour camps.

Henry still has the yellow star with ‘Jood’ printed in the centre that he was forced to wear and which he says he keeps with him ‘as a symbol of strength’. ‘It continues to remind me of the importance and the need for tolerance, openness and the acceptance of others who look different from us,’ he says.

Hiding

In 1942, Henry’s father was arrested and taken to Mauthausen and then on to Auschwitz where, Henry later discovered, he was murdered shortly after arrival. ‘The records they kept were unreal,’ he says. ‘They were proud of what they were doing.’

Henry’s mother made arrangements to leave their apartment in Bezuidenhout-West and go into hiding at a convalescence home with a child care centre on its ground floor on the Nieuwe Duinweg in Scheveningen. ‘If the Nazis were in the neighbourhood, my mother would be feigning some disease and lying in bed, and I would be playing with the kids downstairs or in the little park across the street,’ Henry remembers.

For a long time, Henry thought the place was run by a Sister Frank, who he took to be a nun. However, he recently discovered that he had misheard his mother, and the woman who had found them sanctuary there was none other than Sedje Frank – also known as Sedje Hémon – a key figure in the Dutch resistance who helped many Jews escape to safety in Switzerland.

Deportation

The next part of the story has been erased from Henry’s memory, something he’s always felt uneasy about. ‘I always wondered, how did the Nazis find us? For all I know, I was responsible for it. You know, if they come and ask a kid a question or two, I might have divulged something,’ he says.

The pair were taken to Amsterdam and rounded up at the Hollandse Schouwberg theatre, where during the war some 45,000 prisoners were held prior to deportation. Henry, whose family name is today etched on the monument there along with Anne Frank’s, remembers sleeping on a bench inside the theatre before being housed temporarily at Muiderschans 74, now the Sarphatistraat.

On 15 May 1943, clutching a pillowcase stuffed with toys, five-year-old Henry was transported with his mother to Camp Westerbork, a transit camp to more lethal destinations such as Auschwitz, and known as ‘the gateway to hell’. Here he was housed in the women’s barracks – fairly clean overall, he remembers, and with triple-decker bunkbeds.

Westerbork was run by a Jewish committee which, says Henry, ‘tried to make life as easy as possible’. In December 1943, a simple Sinterklaas celebration with a Sint and Piet was improvised and a small group of children, including Henry, received toys fashioned by fellow interns from wood they had found in the camp.

‘Westerbork was more like a ghetto than a camp,’ says Henry, but it was nevertheless ringfenced with barbed wire, and every Tuesday a list had to be drawn up of around 1000 people to be sent East on cattle cars, never to return again.

Belsen-Bergen

On 1 February 1944, their own names appeared on the list and Henry and Pessel were transported by train to Belsen-Bergen in northern Germany, a concentration camp whose harsh conditions would claim the lives of 52,000 prisoners, including Anne Frank who succumbed to typhus there.

A terrified child, miles from home, Henry recalls ‘getting off the train in Belsen and walking along a long country road with tall trees on both sides [and] Nazi soldiers with huge dogs, bigger than me, herding us into the camp’.

Starvation also claimed lives at the camp and many of Henry’s memories relate to food. ‘We had to stand outside the barrack. We had little tin cans. There would be a big barrel outside with some slop in it they called soup and somebody would ladle some of that soup into each one of our little cups.’

Afterwards, the children were made to clean out the barrel. ‘That was not a punishment, in retrospect,’ says Henry. ‘Probably, while we were cleaning it, we could find a few more potato peels or something for extra nourishment.’ Pessel’s religious observance also kept him from starving. Each meal she would save a scrap of bread to serve on a Friday evening as a Challah to mark the Shabbat.

That no trauma exists in Henry’s memory, he also attributes to his mother. ‘She must have been an incredible woman to protect me,’ he says. ‘Have you seen the Italian movie Life is Beautiful? That’s my story, … taking care of the kid and making him feel like it was a game – my mother must have done that for me in order to keep me sane.’

Salvation

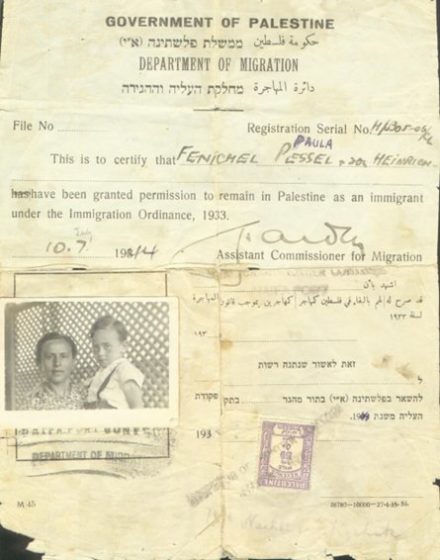

While at Westerbork, Pessel came to hear of a prisoner exchange programme with Templers, a Protestant sect originating in Germany. Templers living in British controlled-Palestine, and now held captive by the British, were to be freed in Germany in exchange for the liberation of Allied detainees with a connection to Palestine.

Since Henry’s father had immediate family in Tel Aviv, there was a chance they might be eligible. When they went into hiding, the Fenichels’ neighbours in The Hague had swiftly occupied their empty apartment to avoid attracting attention to it, and so – crucially – their paperwork was still intact. Despite an initial failed application, Henry and Pessel eventually acquired the registration numbers necessary to satisfy the record-obsessed Nazis.

Miraculously, they eventually found themselves on a special list of just 222 prisoners – mostly women and children – and their lives were spared. ‘If it were not for a few people who saw an opportunity to save a few souls, I would not be here today,’ Henry says.

In June 1944, he and his mother began the long journey to the Middle East on what became known as Transport 222, with little Henry sleeping in the luggage rack overhead, all tied up to prevent him from falling. The German soldiers on the train, fearful that the ghastly truth of Belsen-Bergen would be liberated along with these prisoners, began to sweet-talk the emaciated passengers. ‘We didn’t treat you so badly, did we?’ they said.

The hardship of the camp, however, revealed itself from time to time in the passengers’ behaviour. When a pedlar approached the train selling cherries, for example, Henry’s eyes were like saucers. He had not seen fresh fruit for two years. To a small, hungry child, he says, they seemed the size of apples.

Palestine

The exchange of prisoners took place on water: two boats nudging side by side on the Bosphorus. The 222 then skirted the Turkish coast and made for Lebanon by train. As the Jews crossed the border into Palestine, passengers tried to rouse a chorus of Hatikvah – now the National Anthem of Israel – but it was drowned out by their sobs.

Henry had been by his mother’s side throughout his incarceration, but the Palestinian authorities saw fit to separate the pair for four years. Pessel joined family in Tel Aviv and Henry was sent to a children’s home in Nahariyya in the north. When Pessel remarried, she reclaimed Henry and they set up home in Tel Aviv. One day a truck arrived in front of the house with a huge storage box full of possessions and furniture from their apartment in The Hague. Their neighbours had discovered they were alive and had sent it on to them.

Revisiting

When the family later emigrated to New York, their Brooklyn neighbourhood with its familiar Dutch-style architecture must have been a home-from-home for Pessel. Henry even attended a high school called the New Utrecht.

His curiosity about his birth country never left him and in 1982 he would return to the Netherlands, along with wife Diana and their two daughters, to take up a nine-month sabbatical as a visiting professor at what is now the TU Delft. ‘It certainly felt like coming home in one sense, but I didn’t remember my Dutch,’ says Henry, who spent hours in the university language laboratory trying to revive it.

Henry would also return to Belsen-Bergen as part of a group commemorating the 50th anniversary of Transport 222. The two-mile-long road to the camp was still there, but a museum had replaced the demolished barracks. There was almost nothing left architecturally, but there was no doubt about his personal history when an attendant plucked from a drawer a card with his name on. ‘The day we arrived, the day we left – everything about me was in their records,’ he recalls.

Interestingly, his main response to the visit was not sadness. ‘I actually had a positive feeling when I was there,’ he says. ‘Among the people going around were soldiers … I felt, if that’s part of their education, then maybe there’s hope.’

Reparations

The subject of financial compensation for the Holocaust is sensitive and, as a resentful 18-year-old, Henry initially refused what he was due. But he later accepted Article 2 compensation from the German government and, more recently, reparations from the Dutch railway service NS for their part in transporting prisoners to Westerbork.

Henry, who lives a comfortable life in Cincinnati with a good pension, chose to use the funds as a force for good. ‘I normally give that money to charity,’ he says. The compensation could of course never make up for what happened. ‘I don’t think that brought the subject to a closure,’ he says. ‘You can’t do that with money.’

Three quarters of Jews in the Netherlands, around 110,000 adults and children, were murdered in the Holocaust – the most in western Europe, both proportionally and in total number. But when you hear these numbers, says Henry, it means almost nothing. ‘The history books rarely speak about individual citizens and how these wars affect us,’ he says. Listening carefully to the story of survivors, he believes, is one of the best ways to make good on the past.

DutchNews.nl is marking the anniversary of the end of World War II in the Netherlands with a short series of articles. Next Monday (April 20), we look at the stories of American servicemen who died during the liberation of the Netherlands through the ‘Faces of Margraten’ project.

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation