Black in Rembrandt’s time: a myth-shattering exhibition on identity and truth

A new exhibition at the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam tells the story of the black community in 17th century Dutch society and how the portrayal of black figures in Western art reveals much about attitudes to race.

With a keen eye, surprising discoveries can be made in Jacob van der Ulft’s gouache painting The Market in Dam Square, Amsterdam (1653). Amidst all the loading and unloading of goods, trading and gossiping, are a trio of turbaned men from the East and, mixing in with the crowd at a fish stall, a black-skinned man dressed in blue.

Black in Rembrandt’s Time, which opened at the Rembrandt House Museum on 6 March, combines 17th century artworks and records from the city archives to reveal an irrefutable truth: the Netherlands has been multicultural for some 400 years, and black people – at odds with a myth of monoculturalism – were both present and free in 17th century Amsterdam.

Rembrandt’s neighbours

The black community in Rembrandt’s time were mostly sailors, soldiers, and servants, and were concentrated around the Jodenbreestraat, where the museum – Rembrandt’s former home – stands today. Rubbing shoulders with other migrants from Germany, Portugal, Spain and Scandinavia, was a diverse black diaspora: Africans, West Indians and Brazilians accompanying repatriating Dutch families from the colonies or in service to Sephardic Jews fleeing persecution.

Thanks to the research of historians such as Mark Ponte, who worked on the exhibition, we know that a community of around 80 people of colour were based in the area, representing about 0.4% of the population. Despite widespread slavery in the colonies, the practice was banned within the country’s own borders, and black immigrants – though mostly low in status – were technically free. Records show inter-racial marriages dating back to the 16th century.

Drawn from life

Further evidence that Rembrandt’s contemporaries lived among people of colour is the realistic depiction of black people in their works, most likely local residents who agreed to model for the artists. In fact, it was guest curator Stephanie Archangel’s encounter with Rembrandt’s unexpectedly lifelike Two African Men (1661) that sparked the idea for the exhibition. Archangel, who has Curaçaoan heritage, had always struggled to recognise herself in art museums, yet this 350-year-old oil painting was an exception. ‘They were really proud and they looked like real men, like real people had stood there and that he had drawn or painted them from life,’ she says.

She contacted historian Elmer Kolfin and asked him: ‘Am I seeing something different? Is it real that Rembrandt painted these people more humanely than I’ve seen before?’ Kolvin set her on a path of discovery to works by Rembrandt’s contemporaries: Gerrit Dou, Hendrick Heerschop, and the Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens. ‘It’s not just Rembrandt,’ he told her, ‘but a whole period in Rembrandt’s time.’

Breaking stereotypes

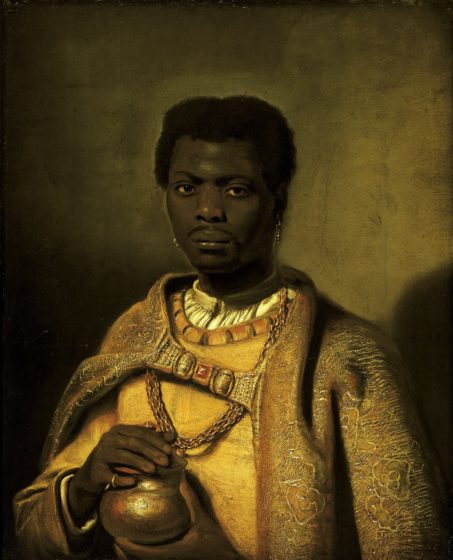

So realistic and familiar was the splendidly dressed man in Heerschop’s King Caspar (1684), that Archangel had the strange sensation that her uncle was looking back at her. Here the black person was not a servant hovering in the background, an adjunct to enhance a central white figure, but the subject itself of the work. ‘It’s nice to look at 17th century paintings and be proud as a black person, instead of uncomfortable or sad,’ she says.

The exhibition’s twist is that these masterful paintings, etchings and drawings are more realistic than the negative, caricatured depictions of black people which came later, and which also feature in the exhibition by means of contrast. Tropes such as the man-eating savage or the eager, smiling slave appear widely on illustrated maps and books of the period and were used to sell exotic commodities such as tobacco and cocoa. ‘It’s interesting to see that there was a period that this was not as dominating as it is now and it really shows how that dominance is something which has been constructed,’ says Archangel.

Naming people

Acting parts in biblical scenes or extras in a landscape, black figures – however lifelike – were nevertheless largely anonymous, and Jasper Beckx’s Portrait of Don Miguel de Castro (1643), which features in the exhibition, is one of the few black portraits where the name is known.

Dutch Masters Revisited, four photographs distributed throughout the Rembrandt House Museum, seeks to redress this indignity by naming and celebrating prominent black figures today. Curated by Jorgen Tjon A Fong of cultural organisation Urban Myth, the series features Dutch celebrities, such as the singer Tania Kross and the radio presenter Humberto Tan, photographed as the subjects of 17th century masterpieces.

Black Jesus

The final section of the exhibition displays contemporary works where black people are both the artist and the subject, speaking their own truth and questioning received ideas about black identity. ‘We are all imprinted with the idea of a white Jesus, even though this wasn’t the case,’ says Raul Balai, who co-curated this part of the exhibition with Brian Elstak. The pair chose a dark-skinned Jesus as the subject of their own art work, which features in the exhibition alongside an oil painting of political activist Hermina Huiswoud and ‘Too Black’, a photograph of members of a ballet company.

Though the impressive art work alone merits a visit, Black in Rembrandt’s time is above all a bid for black visibility and truthful representation, and an interrogation of prevailing views of history. Art exhibitions are no longer just about aesthetics, explains Archangel. ‘It’s become more about the people. Who were these people? How did they navigate society? Rather than just looking at paintings with black people in them.’

Black in Rembrandt’s Time runs from 6 March to 31 May 2020 at the Rembrandt House Museum, Amsterdam. The exhibition is part of Musea Bekennen Kleur, a collaboration between 12 museums to ensure diversity and inclusion.

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation