8 people who are bringing Syrian culture to the Netherlands

From Dabke dancing to Muwashshah music, the Netherlands has a lot to learn about Syrians and vice versa. Deborah Nicholls-Lee meets eight people who are building bridges between the two communities and celebrating the very best of Syrian culture here.

Samer al-Kadri

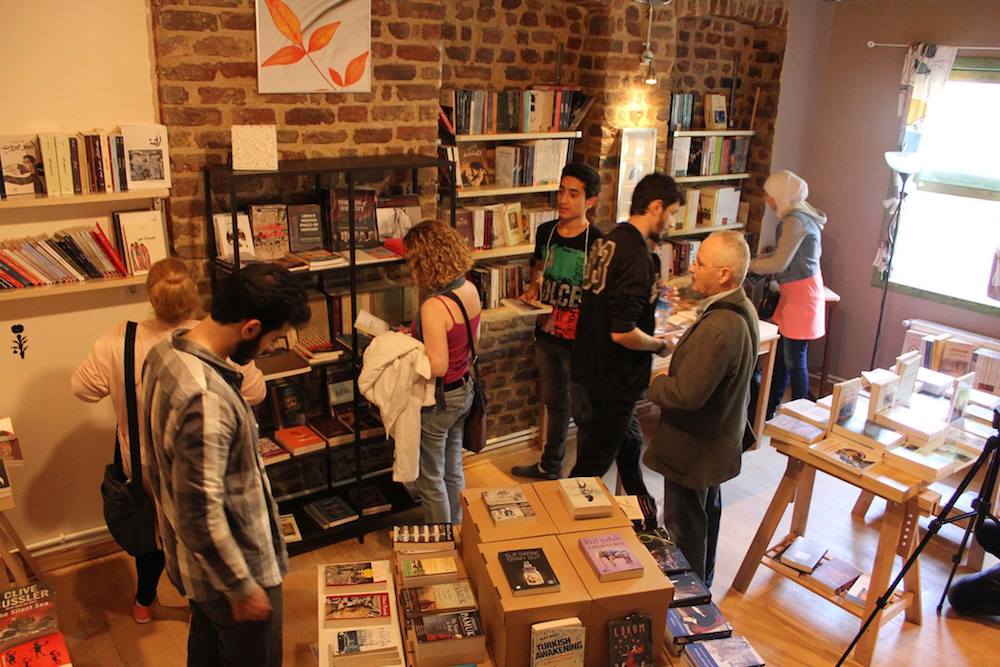

Located in some of Amsterdam’s most expensive real estate on the Herengracht canal, is a place where almost everything is free. Pages Bookstore Café is not a business, says Syrian founder Samer al-Kadri: ‘It’s just a message in my mind that I want to say to the world.’ On June 12, the artist and publisher opens a centre that brings literature, art, music and theatre from the Arabic world and from Europe to a diverse audience to create a place that feels like home to everybody.

Pages Amsterdam is Samer’s second bookstore. Pages Istanbul opened in 2015, partly supported by the Prins Claus Fonds, whose motto is ‘Culture is a basic need’. Samer (42) already has plans for a third branch in Berlin. ‘My mission is to open one everywhere – even in the Himalayas!’ he says, and it’s not clear if he is joking.

While Pages will be, he believes, the only Arabic bookstore in the Netherlands, he is keen to emphasise that it is a multi-cultural space for everybody, with books and entertainment in a variety of languages. ‘This place is not just for Syrians,’ he explains. ‘It is a way for Syrians to introduce themselves…We bring people together from different nationalities.’

This coming together is central to the bookstore’s aim to unite Syrian newcomers with their new neighbours. ‘The new arrival doesn’t know anything about the Netherlands and the Netherlands people don’t know anything about us. And this is very important, to know each other.’ He sees culture as facilitating this: ‘Let’s know each other before we judge each other. And when you do this through fun and art and happiness, it will be better.’

Ahmad Naffory and Claudia Willmitzer

‘People are amazed to listen to something new,’ says Claudia Willmitzer, a German, who together with her Syrian partner, Ahmad Naffory, form the band Coconaff, which is bringing Syrian rhythms to fresh ears in the Netherlands. They met at a gig in Lebanon and decided to share Ahmad’s long and difficult journey for asylum together, moving from country to country until they found sanctuary in the Netherlands.

It was Ahmad who bought Claudia her first Oud, an Arabic lute, which she says is ‘an honour to play.’

They have just released their first album, Cleopatra & the crazy bird. They describe it as a ‘love story’ and an example that something positive and beautiful can emerge from an ordeal.

Ahmad describes the band, which fuses Arabic melodies with flamenco rhythms, as ‘an international mixed band, playing traditional oriental music in a new way.’ He enjoys sharing Arabic music with Europeans and was happy to see the way his British percussionist, Simon Coleman, learnt to play the unfamiliar maqams and rhythms which you rarely hear in European music.

The band sees itself as having an important role to play in bringing Syrians and Europeans closer together and, says Ahmad, aims to ‘break stereotypes and express the right of equality and freedom for everyone.’ Live music, Ahmad explains, is heard in every restaurant back in Syria and is something that newcomers here miss.

Esseline van de Sande

Dutch-born Esseline van de Sande, social psychologist, author, and Middle East advisor, first discovered Syrian culture when she worked for the United Nations in Damascus. But it was a trip with a friend down the Euphrates in a two-person kayak, and their arrival in the ancient Dura Europos (fort of Europe) where she was most struck by its importance and beauty. The monument’s name, she says, ‘is a message in itself’ as Europe is intrinsically connected and indebted to this region through the alphabet, astronomy and mathematics that ancient Mesopotamia brought us.

‘By living there, working there, and delivering my first child in Damascus, I got really into the culture and I realised how little we know about this region.’ Most of all, she was struck by the ‘abundance of generosity’ of the people she met. When war broke out, and many Syrians made the Netherlands their home, she realised that ‘people have no idea who will be their new neighbours.’

Her 2016 book, Ontmoetingen met Syriërs (Meeting with Syrians), was a way to address this and allow Syrians such as composer and music teacher Amer Shanati to tell their story, focusing on their career background. By pairing interviewers and interviewees that came from similar professions, the book inadvertently became an intervention in itself, linking the two communities and providing a useful network for the new arrival.

Esseline is also one of the founders of the Great Middle East Platform, which aims to provide information about the Middle East that people can relate to and give a fuller picture than the one presented in the media. Under the umbrella of the Room of Listening, she and her colleague Shervin Nekuee organise events, such as networking dinners and a pop-up bazaar with music and poetry from the Middle East.

Jurriaan Momberg

‘It’s quite a party to cook together,’ says Jurriaan Momberg, founder of Syrian Chefs, a team of caterers who are bringing the flavours of the Levant to the Dutch table. For 18 years, Jurriaan managed the Ekeko and Soeterijn restaurants at the Tropenmuseum, until, he says, funding cuts forced their closure. In 2015, he saw a Facebook post on Vluchtelingen Amsterdam, asking for a volunteer to help a Syrian cook with transportation. After this, Jurriaan met other cooks who were also at the Havenstraat asylum centre, and his help with logistics, training and networking, evolved into Syrian Chefs, a ‘foundation for every Syrian who wants to cook.’

Sharing food, explains Jurriaan, is central to Syrian culture and is a way of connecting with each other. ‘Wherever you go, there’s a table with food and it’s always cosy,’ he says. ‘How nice is it to be proud of something that comes from your country but makes people happy here in the Netherlands?’

Syrian Chefs are currently investigating plans for their own restaurant in Amsterdam. They will be at the celebrated Food on the Edge symposium in Galway, Ireland in October.

Adnan Alaoda

‘Because of the circumstances in Syria, a lot of Syrians went out to many countries around the world, so it is very important in this time to keep our culture alive,’ explains Adnan Alaoda, a Syrian poet, songwriter, journalist, and award-winning theatre and TV scriptwriter, who moved to the Netherlands in January.

He is currently based at the Verhalenhuis Belvédère in Rotterdam, a cultural centre which aims to bring diverse cultures together and, in association with Icorn (International Cities of Refuge Network), offers shelter to refugee writers. Here he has established Al Rewaq, a concept he founded in 2015 in Dubai, which hosts monthly evenings of Syrian and Dutch entertainment, such as poetry, plays, films, and singing.

‘I know that Syrian culture might be new for people in the Netherlands’, he says, ‘but it is very interesting also to see the beauty in it.’

With Al Rewaq, Adnan hopes to raise the spirits of Syrian newcomers. ‘The important idea is to bring Syrians together again, to inspire them, to make them believe that they can do a lot of important things here as Syrians, and this will lead them to be more integrated with the Dutch community.’

Adnan believes that we have much to learn from each other. ‘It is very important to take advantage of other cultural experiences and to be able to live with other cultures and affect them in a positive way.’ ‘Earth is a place for all,’ he says.

Iris Loos and Tamer Allaloush

‘It’s like you have a best friend that lets you into all aspects of a different world to help you understand,’ says Iris Loos about Syrian national Tamer Allaloush, who she met when they both volunteered at a refugee clothing bank in Utrecht. In 2016, they founded Dreaming of Syria ‘to empower the Syrian community by giving them a stage and also celebrate diversity in the city of Utrecht.’

‘Dreaming of Syria aims to show you another side of Syria,’ explains Iris. ‘And to connect different people by sharing music, history, stories, poetry, food and dance.’ For Tamer, it is important to show how life was before the war: ‘our hospitality, our traditional life’ and the ‘beautiful and lovely country we had.’ ‘It is important to keep those memories alive,’ agrees Iris.

Upcoming projects include extending the Dabke dance nights to other Dutch cities, an Arabic market in Utrecht, and a Dabke flashmob in Utrecht town centre on June 15 to launch the Global Week for Syria. ‘Dabke is just an aspect of Syrian culture,’ says Iris. ‘But it gets Syrians and Dutch [people] dancing together. That’s what we love to see happening.’

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation